In the late 1990s, Bay Area roads were full of cars from the sixties and seventies: Maroon Mustangs, Gold Novas, Orange Karmann Ghias—spewing exhaust up and down El Camino Real in the peninsula suburbs where I lived and went to high school. Like a car would seem from the mid-nineties today, they were old but not quite classics yet and you could still find them cheap at impound lots and in the pages of Auto Trader. My first car was a 1972 VW Super Beetle—robin’s egg blue except for an orange trunk fitted over the engine that rattled once accelerated past 50 mph, blowing the car across freeway lanes in Bay Area winds, all of which was exciting.

The Super Beetles are an abomination to real VW people. A later model, they were slightly larger with plastic moon-shaped vents on the side panels and a chunkier, less elegant bumper. But it drove and it was cheap: $2,500, an amount that I’d saved from a series of fluke radio commercials I’d done as a kid. This Super Beetle was also part of a larger teenaged project of drafting one’s life out of borrowed narratives. In this case, a character detail lifted from a Drew Barrymore movie in which she played a troubled, Beetle-driving transfer student who attends punk shows. By the time I turned 16, I, too, was a perpetual “new girl” and on my third high school. As someone constantly arriving, I needed a way to announce myself quickly and sensed (and still believe) that culturally discontinued objects have a sorting power—sending a rapid signal that intrigues the like-minded and warns off everybody else. I drove the loud car and carried a flower-power suitcase instead of a backpack, which also sent a flamboyant distress signal to all around, something like “I am desperate to be known.” At the time, of course, I thought it gave the opposite: “You cannot know me.” For this was the very image I hoped to cultivate then while adrift in the wreckage of my family.

My constant transfer status was the result of a re-marriage followed by a shift in custody. By sophomore year I was working under the table at a record store (incredibly named The Vinyl Solution, though they insisted the Holocaust pun was accidental) and running away from home periodically, staying with older friends or occasionally on Berkeley streets after shows. I was romantic, defiant, and a little feral. At least one of the moves was an attempt by my mom to separate me from delinquent friends at a prior school which proved unsuccessful—I would quickly fall in with a similar crowd at each successive school. I have especially fond memories of the School #2 stoners, who rode around in a convoy of hand-me-down muscle cars. Each day we would caravan to Randy’s Donuts for lunch, occasionally returning for afternoon classes, but more often going to smoke weed on some hill; there was also the mysterious Pulgas Water Temple through which water from the Sierras flows into the Crystal Springs Reservoir. In the seventies, kids used to jump into the temple with inner tubes and float out into the reservoir itself. By the nineties, we could only stare down at the rushing water through the metal grate and inhale the fresh chlorine, which served as a perfect metaphor for our nineties brand of liberty fused with fantasy—a far less wild reenactment of a past world that felt close but was rapidly receding. The Bay Area still felt like it belonged to the counter-culture, the traces of the recent past being so plentiful then that it seemed impossible any of it could disappear.

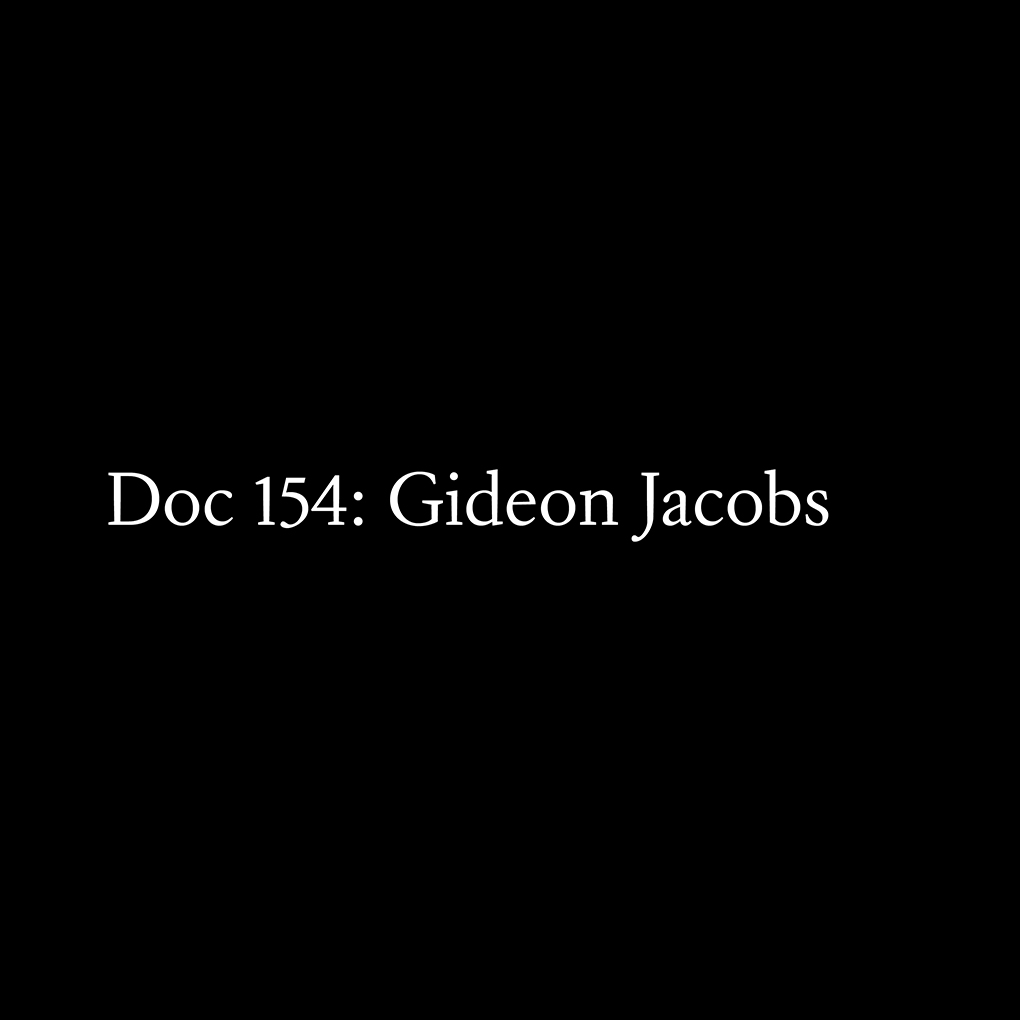

Aside from myself, there were three students with Bugs at School #3 and one was Tracy, a future friend. Hers was lovingly restored by her father and mint green with the original VW flower vase and a roof rack, where, had it been mine, I could have strapped my floral suitcase. My Beetle was, by contrast, disheveled, a rolling symptom of my interior state. For further flare, I guess, I had strung rows of yarn dingle balls across the interior ceiling so that they were visible in the windows. The car may have looked like the site of a carnival to a passerby. By that time, I worked at Barnes and Nobles where I considered theft an employee benefit and my trunk (and bedroom) was overflowing with books and a flood of things found in abundance in thrift stores: Mexican tooled-leather, Precious Moments plaques, metallic decal tees, argyle socks, Avon perfume girls, macrame market bags. A Cure record played continually in my room and a Fifteen tape in my car. It felt like living in no era in particular, which was great, as it suggested an escape from the particular disaster of my own time and family.

While I had technically come to live with my dad after Sophomore year, I lived alone a lot of the time. He was scrambling to get a business venture off the ground in Vietnam, having lost everything in the divorce, and was often gone for weeks at a time. While I succeeded in occupying multiple continuums while driving my old car around, they converged every time I went back to our dirty, nondescript apartment. I remember the electricity being turned off once and staying with Tracy, sleeping in her beautiful house with her beautiful Bug parked outside. Another time I tried to shoplift groceries from Safeway during a period when my dad was out of the country. Eggo waffles and syrup, I recall, were part of the lift. I made it out to the parking lot and almost back to the Beetle when I heard an employee yell across the parking lot “Miss!” and took off running. I ran several blocks and found myself hiding under a truck for a while. When I emerged to peek over a fence at my car, I saw Safeway employees looking through the inside—I had left it unlocked with the keys in the ignition. I waited several hours for the store to close and returned to my car to find they had taken the keys: I would have to confess to get the car back. My keychain also carried my house keys. My older brother, who lived a few towns over, was not amused when I called him collect, sobbing, from a payphone. The store didn’t press charges.

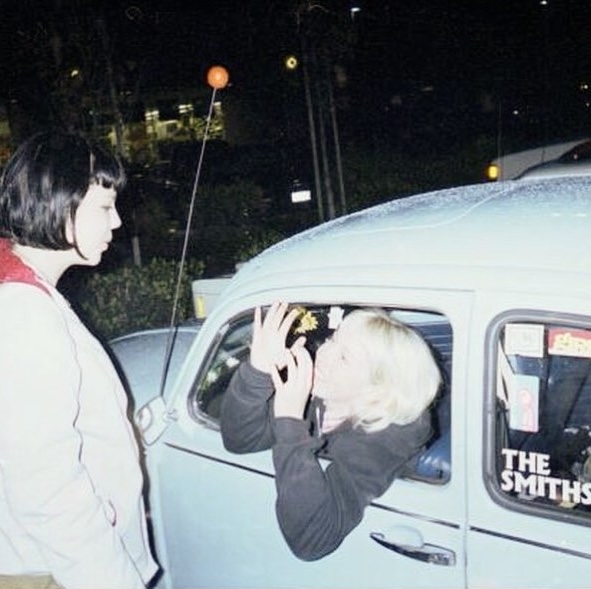

The Safeway incident may have ruined the Beetle for me. A clean slate felt appropriate and I soon found it in a new car, the Valiant. It was a 1966 white Plymouth four-door with a sexy red and chrome interior. It had a slant-six engine and a three-on-the-tree stick shift on the red steering wheel. I bought it from an impound lot called Airport Towing where something about “an engine problem” was noted. The car cost under a thousand dollars which seemed like a decent price for however long the dream would last. I sold the Beetle to a girl at my school, the cost including whatever was in the trunk.

The Valiant really did make me a different person. Through the thick glass windshield, the world took on a different voltage, similar to looking through the ground glass of a camera viewfinder, where everything falls into a beautiful frame and order. Except I was part of the composition—performing the image, suddenly coherent within its frame: a car, a costume, a character.. It felt glamorous. My best friend, Karina, and I had twin bob haircuts, mine was bleached white and hers jet black, and we would drive around smoking and listening to Bratmobile in our fake fur coats and flooded Sta-prest pants. I had grown up some, and was working at a coffee shop right next to my former employer, Barnes and Noble, and had become a somewhat-better employee… apart from inhaling the nitrous oxide from the whipped cream bottles. I was happier, too.

The Valiant’s engine blew one night while driving with my cousin, Brooke, who had been sent to visit me from New York—she was confused why my dad was nowhere in sight and why the kitchen only had frozen potstickers and microwave popcorn. We had driven up to Ocean Beach where friends were having a bonfire when there was a loud burst from the front of the car. We left it on the road and went walking up the beach to look for my friends, approaching each fire and never finding them. We made it all the way to The Cliff House on the North end of the beach and the restaurant let us use the phone to call my friend John. Like many of the guys I hung out with while attending high school, John was not in high school. He was six years older, drove a ’64 Malibu, and may have been a musical genius. He wrote a zine called Joys of Lawn Care with drawings of alternate uses for computers (like keeping coffee warm). I can remember him shaming Brooke that night for liking Aerosmith. For the rest of her trip we had no food and no car. I have no idea how she got to the airport.

The Valiant was eventually towed back to the Barnes & Noble parking lot where a coffee shop regular offered me a 1963 Dodge Dart for a trade. The Dart ran fine if you warmed it up for five minutes—otherwise it would just rumble to a stop—but a working car for a broken one seemed like a good deal, even if it was a hideous teal green. Popping it into drive on its futuristic push-button dashboard was fun, and I appreciated how each car was older than the last, how the mysteries of displacement deepened with each trade—riddles of time and form I had no language for yet.

The Dart marked a new chapter with help from a change of address. My father and I had been evicted from our apartment and moved into a smaller one. The parties I threw while he was away, or the overflowing Chardonnay bottles when he was home, may have been factors. The police had visited once looking for a runaway girl who had been staying with me, but didn’t bother to ask why I was there alone running my own chaotic household. I have the sense this would go differently now, but the cops back then had grown up in an era believing, as my dad likely did, that teenagers are like bumper cars—built to absorb impact.

The Dart got fucked up. While fleeing a party after the hosts’ parents came home, I tore the passenger door off on a mailbox, breaking both the door and the mailbox. My friend Matt claims I nearly killed him too as he was trying to jump into the moving car at the time. I installed a replacement door found at a tow yard, but it never closed properly. A bungee cord helped keep it shut, but was threaded through both windows, which meant I could never roll them up. Friends started calling the Dart, The Coffin, and it only barely clung to life as I warmed it up each morning in cold, coastal fog. Looking back, I was constantly navigating choppy waters back then, driving a dying car to do illegal activities and negotiating total independence before I was remotely ready. Still, the Dart was strange and beautiful, a ragtag spaceship from the sixties. I could pile eight people inside and take them all to the drive-in movie theater, where they charged by the vehicle, before it closed.

At the end of my senior year, I sold the Dart to an older boy I was in love with throughout high school: Jimmy, a beautiful cipher always receding into the same fog; like the 20th century itself, slipping further into itself just as I was trying to discover it. He eventually moved to Alaska and only very recently did I see him again at a mutual friend’s funeral. I think I sold him the car for very little in hopes he would like me more. I didn’t understand desire yet—my own or others. What I was far more successful at, more than anything, was cultivating avenues of escape, transforming talismans and cheap disguises into narratives of onward passage. The dry and cracked tooled-leather purses. The row of empty Avon lady-shaped perfume bottles. The piles of stolen books and thrift-store dresses that turned my room into an archive of other people’s pasts. The cars. They really did open up other worlds that in some sense I never returned from—they were transportive in more ways than one.

Courtney Stephens is a filmmaker and writer based in Los Angeles whose work tends to explore fantasy, belief, and the past. Her films include John Lilly and the Earth Coincidence Control, Invention, Terra Femme, and The American Sector. She co-programs the LA microcinema Veggie Cloud.