2014 (The Age of Style)

“If I could design time, that would be very nice.”

Yohji Yamamoto, 1988

PART I

Masha Tupitsyn: Let’s start by talking about your unique and special upbringing. All the women in your family were artists, seamstresses, and knitters, so art and clothing were fused early on. For a long time, both your mother and aunt made clothes for you. Was this purely because you didn’t have money to buy the clothes you liked? Did you design them together? When I look at some of those clothes now in photographs, I think of them not simply as articles of clothing, or even examples of innovative style, but as art objects. And I still wear a lot of those pieces myself because they’ve lasted. Where do you think style comes from? Where does yours?

Margarita Tupitsyn: Most Russians were really poor, so they couldn’t afford to wear the high fashions of the West. But there was also simply nothing to buy in the department stores. The only people who dressed well were people who had access to the West or who made their own clothes. On rare occasions, things were brought from abroad and people would stand on these long, horrible lines to buy something. And most people didn’t have any money anyway. In my case, my mother, grandmother, and aunt compensated for that absence by making basic things for my family and me to wear. My aunt, the painter Lydia Masterkova, was a different story, however. She could sew, but that was not her primary vocation or interest. She was an abstract artist, and therefore had an avant-garde approach to form and could make anything—clothes, jewelry, furniture. If we think of the history of the Russian avant-garde in the 1920s, where design played a dominant role, often even overshadowing painting, my aunt was steeped in this tradition. She also liked to dress me in vintage clothes dating as far back as the nineteenth century. She loved Fellini’s La Strada, which was a big hit in Russia in the 1960s, and would style me as Gelsomina, played by the actress Giulietta Masina. Lydia gave me all these identities and characters through clothing. Of course she also made clothes for herself and was always amazingly dressed. She was a feminist, which she, funnily enough, also expressed through clothes. Married to the abstract painter, Vladimir Nemukhin, she had this rule that whenever he needed his shirts ironed for some important party, she would only iron what you could see! She wouldn’t bother to iron the part of the shirt that was hidden underneath the jacket, like the sleeves. So my aesthetic sensibility came from my aunt and uncle, who collected antiques and had completely unusual and atypical objects in their homes. They showed me beautiful art history books with amazing Renaissance paintings.

Masha: So what role did fashion play in the Russian avant-garde of the 1920s, and how did it influence artists like your aunt and uncle later on?

Margarita: Russian avant-garde artists believed that fashion should be egalitarian, part of everyone’s life and that all things should be beautiful and aestheticized. They were against fashion as elitist. Artistic creativity was a way to realize the utopia of beauty and refinement. But after Stalin’s regime of violent repression and unprecedented austerity, this sensibility was lost as a social standard. My aunt subscribed to this ethos of aesthetic coherence because she could make things herself and because she had this incredible eye. She believed one’s whole environment should be cultivated. And, of course, rich people had always pursued this idea of the total environment—the difference being much of this luxury was economically driven. But for my aunt it was part of this artistic, bohemian ideal.

Masha: We know that people can be very interested in aesthetics in a way that is compartmentalized. For example, they might go to a museum to appreciate art, but have no interest in clothes or in surrounding themselves with so-called beautiful objects. Or, they might decorate their homes but not their faces or bodies—so very heightened and cultivated aesthetics in one area and inactive aesthetics in another.

Now, of course, with the prominence of the nouveau riche model of insta-fame and wealth that entertainment culture has made more visible, this idea of refinement and deep style has been further degraded because there is rarely a personally fostered relationship to aesthetics over time. Now we have a consumer mentality. Wealth is composed of cheap status signifiers you can purchase anywhere. You have no idea what you’re buying, or why—only that it is “expensive” and brand driven, even when it’s fake. Before, wealth had everything to do with worth, taste, and exclusivity. When you had something beautiful, however corrupt it was to acquire that beauty—and it’s always been corrupt—you had it because you knew having it meant something. Wealth and beauty are not about what lasts anymore, or where something comes from, or even what it means to you. New equals value. Upgrading reigns supreme. It’s the gaudy cost of things we’re seeing, not the value.

Margarita: The ’50s, ’60s, ’70s art world in Europe and America, but also more generally too, could not afford the clothes that movie figures like Audrey Hepburn or Jackie Onassis were wearing. The art world was poor, so art and glamour were still separate and distinct. The ’60s can be compared to the 1920s avant-garde because the ’60s were a rebirth of those incredibly innovative ideas—the notion of all-around elegance. The art bohemia of the ’70s boycotted glamour; they did not stake their identity in clothing. Artists were doing conceptual things. It was about the dematerialization of an object, dematerialization of clothing, the politicization of everyday life. So decorative and aesthetic indulgences just didn’t matter to them. And then in the ’80s, it changed again. Clothing became synonymous, as you point out in your essay, “Mixed Signals” on Pretty in Pink (1986), with identity. It mattered. If you wanted to be visible, you had to dress in an interesting and radical way. You had to communicate your ideas through dress. People in the art world started to pay attention to how people were dressed and that’s when Japanese avant-garde designers like Comme des Garçons, Yohji Yamamoto, and Issey Miyake appeared. In the mid-’80s, my style changed drastically. Before that, my mother had been sewing patterns based on designers like Valentino and Dior for me to wear, and while some of those clothes were beautiful, they never really suited my sensibility, and my husband, Victor Tupitsyn, who has an incredible eye, knew that even before I did.

In 1984, I bought a pair of shoes at a department store on 57th street in New York, without knowing they were CDG. And then later, I was walking through Soho one day, in 1985, and I saw this totally minimalist store, fashioned out of gray concrete with nothing in it but a few racks of black clothing (CDG’s first store in the ’80s was on Wooster Street, which opened in 1983), and I looked at the clothes and felt the way I did during my childhood—that clothing is art rather than something you simply cover or gender your body with. The clothes reminded me of what my aunt was making as far as formal invention is concerned. I could hardly believe it, and from that point on, I was stuck on Japanese designers.

Masha: There is a moment in Wim Wenders’ film on Yohji Yamamoto, Notebook on Cities and Clothes (1989), where Wenders remarks that when he put on Yamamoto’s clothes “something was different.” Right away, Wenders says the clothes felt new and old at the same time. “I was wearing the shirt itself and the jacket itself. And in them, I was myself. I felt protected like a knight in his armor.” This made me think of your interest in Japanese clothing in the ’80s and also how I learned to wear clothes from you. This idea—of something feeling new and old at the same time—has always been my favorite quality in art, as well people. The idea of honoring tradition while breaking new ground. There is another moment in the film when Yamamoto looks through August Sanders’ People of the 20th Century, a book both he and Wenders love, and observes that the people have “exactly the right faces and clothes. Their clothes clearly represent their business and their life.” Yamamoto is referring to a kind of perfect harmony and synergy between form and content. What Wenders calls “a craftsman’s morals.” Not the total arbitrariness of today, where you can’t tell anything about anyone. Clothes, much less behavior, aren’t meant to signify anything coherent, revealing, or cohesive about someone. Of course, this might seem like a contradiction given Yamamoto’s love of asymmetry. But asymmetry, he says, is the mark of the human touch. “We have to make the true chair, true jacket, true shirt.” Yamamoto goes even further, suggesting that there should be an apprenticeship for teaching these morals, in order to pass them down. To endow others with moral skills. I love the idea of moral or honest clothes. “Not consuming clothing, but living with clothes,” as Yamamoto says. It’s a very beautiful idea, especially given how corporate and corrupt the fashion industry is now. It also makes me think of the saying, “The clothes make the man,” which is backwards. It’s the person that makes the clothes. This is the definition of style, I think.

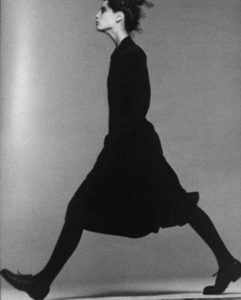

All this to say, I can vividly remember you picking me up from school wearing your first CDG ensemble. I was maybe seven and everyone was staring at you and I couldn’t figure out why. Suddenly you dressed differently and your hair was gone. I think you had just cut all your hair off. This was the age of big, long hair and bright colors and shoulder pads, and you were dressed in spartan black and looked like a boy. The clothing really confused your gender and perplexed everyone. Everyone at school, or even the supermarket, would ask me if you were my brother. I could tell how much those clothes excited you. It was a total shift, but also an organic one. However, while you discovered your style utopia, I also felt that the power and radicality of what you were wearing, and its effect on others, was profound. And yet, I never felt embarrassed by you. I always felt pride. I knew, somehow, that those choices and gestures were an essential part of your individuality and thinking, and that it would be to mine as well. I also remember having postcards of Christy Turlington wearing CDG and how unadorned and laconic those early fashion ads were. Like the reality, the ethos, was the clothing, as you said. The clothes were a state of mind—a social and intellectual value system. How you lived, not just how you dressed—a very Zen precept. That’s why there is nothing else in the background of these ads. No commodity-relation or affect, as it were.

Margarita: Yes, there was a mindful austerity and asceticism to these clothes; no accessories, visible makeup, or fashion “scenes.” Everything was stripped down to the bare essentials, while in today’s consumer economy aesthetics function as pure excess and entertainment proxy. There is also the fact that people essentially stopped paying attention to avant-garde clothing and avant-garde principles and ideas. I remember when I wore Jean Paul Gaultier in the ’80s, who was also radical at the time but in a very different way from Japanese designers, people would stop me on the subway to ask me if I was wearing a costume. The only time I didn’t get stopped was on Halloween. There was something powerful and shocking about being outrageous or different. The result was that people were surprised and curious. A lot of this has to do with the problem and proliferation of the copy and of the mass-marketing of “style” in general, which is an effect of mass production and entertainment culture. You can reproduce anything and recirculate it endlessly, both in images and in copy. When you copy something and make it available everywhere, the originality and effect degrades. So again, while that utopian Russian idea of the egalitarianism of design is a great idea, it doesn’t really work in consumer culture. When promotional culture tells us where to get high-end designs for cheap, how to recreate high fashion looks, and everything turns to cheap affective labor, we lose the personal value and durability of things. We lose the source—the context—of why and how that clothing functions and why we choose to wear one thing and not another.

Masha: But now we have an additional problem—we have branded and over-styled literally everything, so there is no real individual style anymore and therefore no real thrill in discovering style—a neighborhood, a house—or dressing up. Hence, the proliferation of stylists and decorators everywhere micromanaging and mediating our tastes and interests. If it doesn’t result in difference, it’s very hard for me to understand the point of wearing something. As much as I love and have always loved clothing—it’s in my DNA, as it were—style for me is fiercely personal. It is about discovery and finding your own look. I learned that from you. Now everyone knows what’s what and who’s who and who wore what to what and where to buy it—everything is worn in a very meta and branded way, which has made me feel very ambivalent about the power and value of style. So given this total appropriation, what’s the point? I like beautiful and interesting things, but I no longer believe in the power of aesthetics as something outside of commodity culture. What are your thoughts on this, especially in the context of art and aesthetics?

Margarita: The worst thing that’s happened to our concept of clothing is this all-pervasive concept of sexy, of women having to be uniformly and excessively sexy, which is what Japanese designers defied by de-sexualizing and de-gendering clothing. For them, clothing was about expressing who you are through clothing, not simply signaling cues of desirability. The clothes concealed women’s bodies and distorted their shape, so that even if you were thin, for example, that wasn’t the point. You didn’t have to show that you were thin or what your body actually looked like. The clothes were formeless.

Masha: Exactly. You didn’t have to parade the body or some ideal of the body. Avant-garde clothes, but even just the voluminous, asymmetrical, baggy, slouching shapes of mainstream ’80s clothes, which carried over into the ’90s, did not present straightforward representations of the female body. It wasn’t some rudimentary outline of tits & ass. Now, if you have large breasts, you have to wear tops that showcase your breasts. If you have what the culture has determined as a “nice” body, you wear form-fitting clothes. And with Sex and the City, you must always wear heels now to sexualize and advertise your legs, for example. It’s all gone very basic and into this normative direction. That cynicism and commercialization of alternative culture has definitely affected my relation to clothes. It’s disenchanted me.

Margarita: I always dressed for myself. Wearing those clothes was a very strong part of my psychology. Of feeling happy, feeling confident. It was not only my uniform; it was extension of my creative and intellectual sensibilities. Your dad always said that I mopped the floor in my best outfits, which means those clothes were not simply about “dressing up,” or going out, they were fused with my everyday life. They were practical. Whereas today clothes are trophies and status symbols—it’s who’s wearing what with what and how much it cost and getting photographed in what you wear to some social event. It’s how their body looks. So, while Japanese designers like CDG de-emphasized schisms between everyday life and glamour, rich and poor, inner and outer, male and female, celebrity culture re-emphasizes all these norms and binaries even when they pretend to be dismantling them.

Masha: I used to do that, too—paint or clean my apartment in my best dress. As a result, I ruined a lot of clothes with paint and bleach stains! But, as you say, I just couldn’t take those things off because psychologically they were part of me and what I was doing. For me, clothes are internal, not just external. Clothes framed things psychologically and put me into a certain kind of mood.

Why do you think some people lose their style? Does it simply have to do with the individualism, rebellion, experimentation, and aesthetic freedom that sometimes comes with youth? We were talking about Johnny Depp yesterday. How elegant he used to be, along with Winona Ryder, his girlfriend in the early ’90s; how their style was part of being anti-style in Hollywood. There was also a default stylishness built into the culture until about the mid-90s, which meant that a lot of actors, artists, and musicians had style just by virtue of the implicit style embedded into the arts—even the mainstream arts—at that time. I see that with bands all the time. You can always check whether someone has true style by how they look and dress after the culture at large degraded after the mid-90s. Case in point, Depp is so tacky now. As you say, many once-transgressive and stylish people rejected hierarchies of taste and embraced tackiness, outrageousness, and shock value. Is that what Depp is doing? I can’t tell. I don’t see any resemblance between his former self and his current self. His aesthetic trajectory is incoherent to me.

Margarita: Again, I think one of the biggest problems today for artists especially, is what and who influences us, and also the loss of milieus, traditions, and social attitudes. We are influenced solely by media and promotional culture now, more than actual coteries and meaningful social interactions. One of the reasons Winona Ryder and Johnny Depp had interesting style back then has a lot to do with the stylistic framework of the ’90s—the last moment for alternative culture in America. When they wore those clothes, they were open to possibilities. And they obviously had great, raw taste. They were still sort of outsiders in the Hollywood industry—half in, half out. But as soon as you become fully enmeshed in an industry and develop a very specific public image and status within it, which is what always happens with fame, then of course celebrities get schooled on what they should do, how they should act, how they should look. And that’s part of the process of fame and the horrible victimization of one’s identity that happens with it. You lose what is personal in order to appeal to the everyone. That’s what fame is. For me, clothing should be one of the key markers of independence, and famous actors inevitably become dependent on the currency of their images, which can only be under one’s control for so long. Over time, Ryder felt that her wealth, success, and style should be signified through wearing and being styled by, what I would call, “post-designers” like Marc Jacobs.

Masha: What’s interesting about Depp now is that he still sees himself as some bad-boy bohemian, but of course his so-called outsiderness reeks of being bought, which is maybe why it’s so tacky now? There is nouveau riche and there is nouveau style, hence the saying that you can’t buy style. This takes us back to the fake and the copy you were talking about earlier. Why do you think we used to believe in the identity of clothes (with avant-garde designers, etc.), and the identity of who was wearing them, but don’t now? Is it simply because of the commodification and gentrification of everything?

Margarita: Today, everyone, artists included, aspire to be part of the mainstream. There is no alternative culture anymore. No outside. In the past, being against the mainstream—being critical of it—was what motivated radical artists and thinkers. A good recent example is Alain Badiou’s public admission that he wants Brad Pitt to star in his film about Plato rather than some (French) character actor, let’s say. Even Badiou wants to be part of Hollywood. It suggests that even Badiou feels that outsiderness has no real power or value anymore. Like everyone, he seems to believe that his ideas can only be validated through conspiring with the culture industry.

Masha: Yeah, we don’t have many serious role models left. Everyone wants total visibility and fame. Even when someone is stylish, it doesn’t feel individual or personal. I now feel like I don’t know why people wear what they wear these days. It’s arbitrary.

I’m interested in style as distance, in the aesthetics of distance, which I learned from you, both directly and indirectly. For me, style as opposed to fashion or trend, is really about finding yourself. Another recent example of this culture industry complicity is Jay-Z’s six-hour “Picasso Baby” at Pace Gallery, which has him dancing around with Marina Abramović, among others— the clip went viral. In fact, someone was just watching it on their laptop next to us in this café in Paris, where we’re talking now. Art has become completely tied not just to promotional stunts and spectacles, but the desire for celebrity and institutional alliance. But, as you point out, it used to be highly problemaic to have such commercial motives if you were an artist. Of course, Warhol changed all that.

Margarita: Another issue is the fear of being defined as bourgeois, a fear no one in the art or literary world has anymore. In the past, if someone was too well dressed or lived in some lavish apartment, they were considered bourgeois, both aesthetically and intellectually. This bohemian fear, of course, was subverted, as you say, by Warhol who said there is nothing more bourgeois than being afraid of being bourgeois.

Masha: That’s funny. This statement is of course very dialectical, both true and untrue. If your Aunt Lydia was your earliest influence, you and cinema were definitely mine. I remember being obsessed with using clothes to fashion certain identities and outsider positions for myself from a very early age. Posing as these characters—usually androgynous, loner boys from movies—like James Dean and Ralph Macchio from The Outsiders. I wore what and who I felt I was inside. And, of course, my whole sense of style came from inside (i.e., my family, hand-me-downs, movies) as well, from you and dad. So, style was completely linked with my internal life for me, something originary. I always saw clothes as a way of being different, and like you, used them to emphasize—not mask—my difference; to protect it, even when it cost me popularity and social acceptance, which it often did. I never saw clothes as a way in. I saw them as a way out, and you always encouraged that. I can’t remember you ever telling me not to wear something and sometimes what I wore to school was pretty weird (different colored socks; mismatched earrings that I made myself; ripped tights; different sneakers on each foot; crazy haircuts). My fondest memory of your style influences on me was dreaming about going to the Oscars in one of your outfits to accept an award for Best Actress. It never occurred to me that I would have my own clothes as an adult and that time would inevitably change what I would wear! I wanted to wear your wild outfits like Cher in her Oscar dresses in the ’80s. I loved her then. No one dresses like that now, and if they do, it’s a promotional stunt dreamed up by a chain of stylists and PR people—like Lady Gaga. The difference is: I believe Cher’s outfit; I don’t believe Gaga’s.

So there are a few photographs I wanted to look at with you now that document how your style evolved over the years. Can you take me through some of these pictures?

Margarita: Sure.

PART II

Masha: Tell me about this “all red” photo? Where was it taken, what year, and what are you wearing?

Margarita: This is me at the opening of the Sots Art show, which I curated in 1984 for Semaphore Gallery in Soho. In the background is a fragment of the painting by the Russian artist Aleksandr Kosolapov. In this photo I am still taking advantage of my aunt Lydia’s designs. She made this outfit. I’m still in my pre-Japanese designers phase. Lydia is applying Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist, geometric forms to clothing. She would also make accessories for the clothes. As you can see, I am wearing her earrings in the photograph. So the idea of “total” design is being taken from the Russian avant-garde—the idea that everything, when it comes to style and design, has to coalesce. You can also see that my hair is already shorter, and cut asymmetrically, echoing the clothes and the earrings. It is not cut off completely yet, but it is no longer the classically long hair I’d always had before that. When I was at the CUNY graduate center, studying for my PhD in Art History with Rosalind Krauss and other important art historians, my classmates would always comment on my long hair and how it made me look like a pre-Raphaelite. So, to reject this, I started cutting my hair shorter and shorter.

Masha: You were already subverting classical notions of female beauty to spite your beauty. I love this next photo, where we’re looking at each other. This is in Moscow, during Perestroika. We are at the opening of Iskunstvo, an art exhibition of German and Russian artists. The title, as you explained to me, is a play between the German and Russian word for art. You and dad had moved to Moscow for a year to work on the Russian edition of the Italian art magazine Flash Art, and you were also publishing your first book, Margins of Soviet Art: Socialist Realism to the Present. We had just come from Milan, where we lived for six months, and where I became interested in clothes in a way that was also feminine, not just masculine or androgynous. I stopped being a tomboy in Milan. I grew out my hair and became obsessed with knee-highs and tights, which is an obsession that continues to this day, one that you and I both share. In this photo, you’re wearing a fabulous nautical-inspired Jean Paul Gaultier dress, which I now have. You’re also wearing the Italian designer Emilio Cavallini. This is an interesting photo because it shows another side of your aesthetic. All your hair is cut off now, but you are not just wearing austere Japanese designers. You also wore “sexier” designers like Gaultier and Dolce & Gabbana and Romeo Gigli, a great ’90s Italian designer, who played with ideas of sexiness. But with Gaultier, and especially in your case, you deconstructed and subverted femininity and sexiness by pairing it up with the more austere and cerebral contemporary Japanese clothing you wore. You never played it straight, as it were. You always made sure to combine different aesthetics. For example, you would wear that amazing red satin Gaultier bra top, with the pointed breasts, which you did before Madonna, by the way, but with some austere clownish black CDG kulats. Also, look at the knee-highs you’re wearing in this picture—the garters are on the knee instead of the thigh, which I find really smart and funny.

Margarita: Yeah, those knee-highs were amazing. But I am also wearing these big ’60s-inspired glasses, like the ones you wear now, and that ’60s pillbox style bag, so there are all kinds of styles at play. I don’t know why I didn’t keep those gorgeous Cavallini shoes. What happened to them? But anyway, that’s what was interesting about all these different influences. It was an interesting period for Italian design, too.

Masha: Right, the kind of dresses you see Sophia Loren wearing in neo-realist Italian films, which of course wasn’t cheesy at the time but quite elegant. Or Brigitte Bardot. It had elegance despite being a hyper-feminine exalting of the female form. You see this in Fellini films, too, though Fellini always had a kind of early Gaultier approach to beauty ideals—he always made everything beautiful grotesque or strange, like with Masina in La Strada, as you mentioned earlier. He deformed beauty. One of the problems is that famous design labels have been taken over by a new generation of designers, with entirely different backgrounds and aesthetics, so the aesthetics of Chanel and Gucci, etc., totally shifted, the original context severed. These fashion houses were not yet these super corporate conglomerations of mass-produced, mass-circulated brand designs.

Margarita: And the new incarnation of designers have only ever worked in that kind of corporate structure, so they are jaded from the start, and don’t even fully cultivate or oversee their own designs. They treat it as a business and corporate brand first and foremost, and a creative endeavor second. The aesthetic is fractured into a lot of unseen forces—input—but only one person takes sole credit. And because couture, or at least the circulation of it, is now mass-produced and infinitely copied, the people who design it don’t have a sense of the value of originality and quality. Moreover, because they don’t have any real creative control over it, they no longer feel obliged to design well. Trends intensify and accelerate and quality degrades. It benefits the design industry as a whole. They know all their designs will be copied by chains anyway. The gap between original and mass-produced, between quantity and quality, is getting smaller and smaller. Nothing is made well anymore, and if it is, it costs a fortune and only the richest people have access to it. But it is also important to point out that different things look different on different people. It’s not just total style, it’s total effect—context. We’re constantly being told what looks good and what people should wear. What I used to like about shopping at Japanese stores like CDG is that they were empty. But more importantly, I was left alone. They didn’t try to sell you things. Nor did they pamper you with lies about how you looked in something when you tried it on.

Masha: You had to form your own opinion about what you were buying and wearing. Form your own personal connection to style.

Margarita: Yeah, the shop assistants wouldn’t say anything. If someone tells you that you look good in something, but you don’t feel it, it doesn’t really matter what the thing itself looks like or how great it is. It’s a sales pitch. I remember in the ’90s already, when you would come to the Yohji Yamamoto store in Soho, the shop assistants started doing that. Being bothered, or aggressively “sold” something went against my approach to style. I wanted to experience clothes like a work of art—thinking about it, contemplating it. I wanted to decide if I liked something myself. Contemporary Japanese designers were the same way; they were sort of copying this ascetic, gallery-distant attitude. It was bad taste in galleries at that time to jump on viewers who came to look at the work. It’s propaganda, which is what fashion—and art—has been reduced to. If you tell people that everyone will look good in the same things, it’s propaganda. It’s conformity. It’s advertising.

Masha: It reminds me of that famous Pygmalion scene in Pretty Woman (1990)—a little nod to Preston Sturges’ The Palm Beach Story, I suspect—when Richard Gere gives Julia Roberts his credit card to buy an entire new wardrobe on Rodeo Drive. She’s completely redecorated like a doll by the shop assistants who had previously refused to sell her anything because of the way she looked. All the aesthetic choices are made on her behalf, which is treated as a celebratory, triumphant moment in the film. Vivian has finally passed for a “real” lady. But I preferred the way she way she looked before! At least those “sex worker” clothes were her choices. Her reality. Being dressed up—impersonally styled by everyone at the store—is perceived as the highest mark of flattery and economic privilege—an indoctrination into polite bourgeois society and traditional femininity.

Margarita: But that’s a very important issue that we discussed yesterday. The fact that everyone gets dressed up by “tastemakers” now. The minute people have money, they stop dressing themselves. There is a loss of autonomy and agency that happens with fame. These tastemakers are only concerned with making money and bringing money to the designers they promote. It’s about affiliations and promotion rather than attitudes and preferences.

Masha: In an interview about his early anti-fashion Culture Club looks, Boy George stated, “Most fashion is about wearing money.” Which brings us to the idea of the mainstreaming of the avant-garde and the mainstreaming of style, which while good in theory, as you point out, in consumer capitalism has killed individual style and aesthetic agency. There is a whole industry behind teaching people what to wear now and “making people over.” The modernist idea in the ’40s and ’50s, by all-around designers like Eames, was that you could mass-produce quality. It was believed that everyone should be able to own beautiful things for not a lot of money. Now it’s the mass production of cheapness, which is, in fact, not a democratization at all. Most people have shit and only a few people have quality. It’s actually a widening of the gap between those who can have well-made, durable things and those who can’t. What is built to last and what is built to fall apart. And getting things cheap always means there is an increasingly long global chain of exploitation.

Margarita: Bauhaus envisioned this affordable model of quality before Eames. Take Mies van der Rohe’s furniture, which is now very expensive but was originally meant to be affordable. And yet, his furniture was always the property of rich people, so that ideal only functioned in theory in this case. But as I was saying yesterday, the Russian avant-garde and Bauhaus had this utopia of good taste, of quality mass-production, but this utopian vision has obviously failed. It ended up being generic and shoddy, like IKEA. Nothing at IKEA is built to last in any sense. In fact, it’s disposability that has come to stand for quality and style.

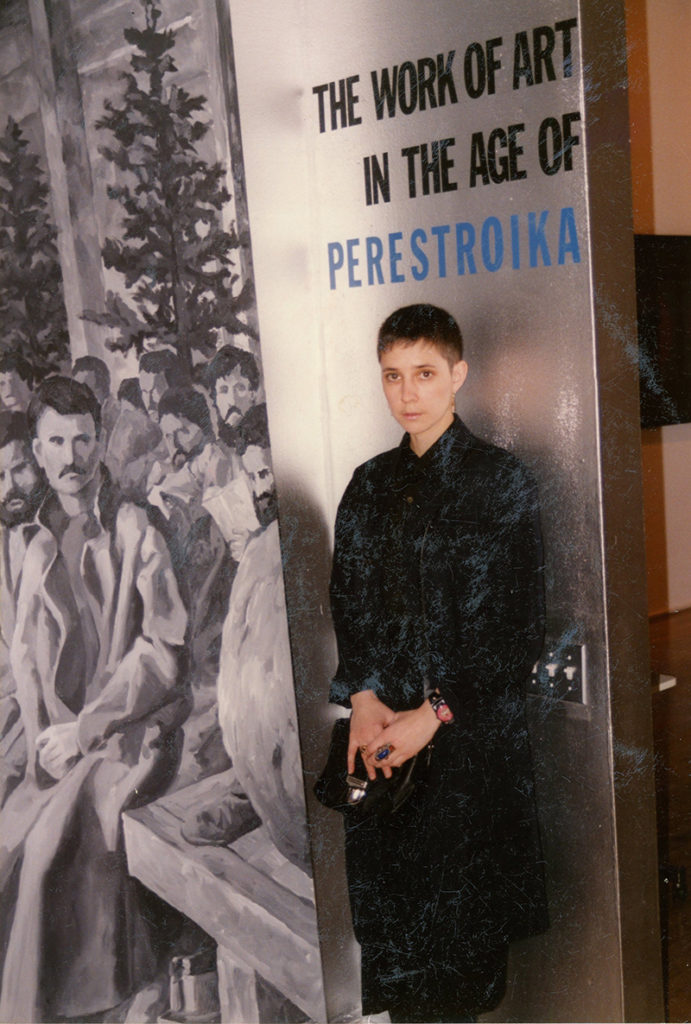

Masha: And what about this final picture?

Margarita: This is me at Phyllis Kind gallery in Soho, where I curated my exhibition, “The Work of Art in the Age of Perestroika” in 1990. The painting I’m standing next to is by the artist Vadim Zakharov and Viktor Skersis. Here you can see that my style has once again completely changed. I look like a little boy! My hair is cut off, and I was only wearing Japanese designers at that point. This is the black CDG raincoat that you wear now, by the way. It’s a men’s coat. But again, I am wearing a Constructivist-style red Russian watch and a big blue ring that Lydia made. But what’s interesting is, at that time, in 1990, it wasn’t just about looking good or cool, or having some hip style, like it is in the art world today. It was more about wearing things that reflected a personal attitude—a little bit severe, conceptual, intellectual, critical—grouchy! So these clothes conveyed that internal stance. It was important for me and other artists and intellectuals at that time to wear clothes that reflected how we felt and thought. These clothes were my identity. The identity of the art world in the ’80s and ’90s was probably the last time when this was true.

Masha: I wear that trench coat now. Every few years I have to fix it with a tailor. It is one of my favorite pieces of clothing. For me, the ’90s were really important because I was lucky enough to be a teenager in a still relatively culturally dynamic and nonconformist time. There was still some possibility of an alternative culture, so my sense of identity, femininity, and style wasn’t being completely mediated or prescribed by corporate consumer culture. Being independent was still really important to me and everyone I knew. Today even much of the subculture comes from some highly visible and branded place. Granted, I know a lot of my sense of personal autonomy and freedom as an adolescent came from being a New Yorker, having you and dad as parents, going to LaGuardia, a public art high school, where being different was actually encouraged, so I never felt any pressure to be anyone other than myself. Everyone hung out with everyone—a very rare high school experience, I know. Obviously, that played a big part in my personal and creative development. Nevertheless, I do see it as a profoundly different time.

This interview is featured in Time Tells, Vol. 1 (2022), Masha Tupitsyn’s forthcoming book from Hard Wait Press.

Masha Tupitsyn is a writer, critic, and multi-media artist. She is the author of several books, most recently Picture Cycle (Semiotexte/MIT, 2019). Her films include, the 24 hour Love Sounds (2015), DECADES, an ongoing film series, The Musicians (2022), and Bulk Collection (2022). Her new book, Time Tells: Time, will be published by Hard Wait Press in November 2022.