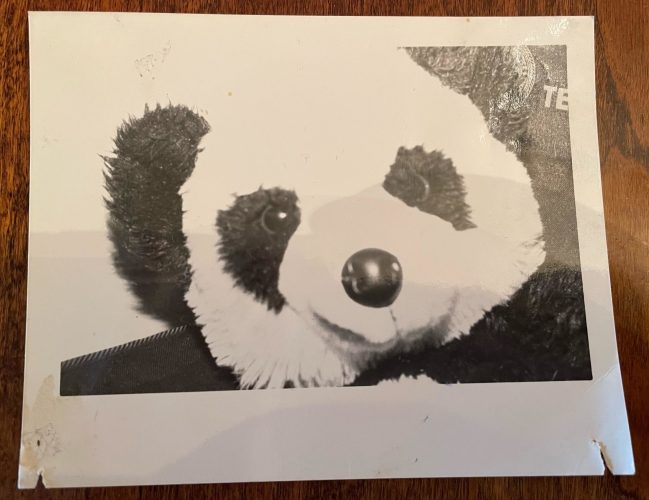

Recently, instead of sitting on my couch, head in hands, wishing a migraine away, I found myself sitting in the passenger seat of my father’s Chevette, pulling a stuffed animal lamb dressed in maroon velvet overalls from the glove compartment, Bob Dylan’s son on the radio. Just as I went to nuzzle the well-dressed rabbit under my chin, I was on the floor of a different room, the one I once shared with my brother, letting a stuffed alligator and a bear named Betty act out their namesakes’ role in “You Can Call Me Al.” And as that lizard began to see angels in the architecture, I departed from the chicken area rug, now rolling down a hill at the park, aware that the friend beside me had seen my desire to leave a painful depression behind, had looked at that hope without comment, offering instead a hand, some books of philosophy, Prince’s complete discography, and a boombox, all of which she was currently dragging in a red wagon, age inappropriate, that we had just won at the raffle for the Catholic church where she had agreed to be my plus one, a friend who will not only go anywhere, but will also conspire to find whatever extant pathways to a good time the place offers. Then Space Panda, who used to appear in my dreams, fishbowl on head, and take me to Martian bamboo field.

In this waking, sober hallucination, the prior easy comforts of my life continued to parade before me, as if someone had found my childhood diary, tied me up, and read it aloud. The stuffed animals and favored pens and re-read books and borrowed CDs and VHS recordings of Alice in Wonderland and speech therapists and cool kids who had pretended not to notice all manner of things about me, or who liked what they noticed, kept coming, sometimes real enough to worry me it was psychosis, though mostly safely under the category of “memories.” I felt: I have had it easy and many comforts have come and gone.

A surprise side effect of nicotine withdrawal, these visions honestly helped. The part of my brain usually reserved for bad thinking—idiotically punishing self-criticism, intrusive thoughts about food poisoning, replayed party chatter—had been repurposed into a friendly drive through my past security blankets. It was a scene from a relatively cheesy fantasy show, and it was, at times, pretty funny: imagine trying to write an agenda for a committee meeting, but you can’t see the computer screen because you’re too busy visualizing, against your will, the giant bunny with whom you used to co-sleep.

In any attempt to quit nicotine permanently, the smoker or vaper (or gum-chewer or lozenge-sucker) confronts a self-narrowed pair of possible futures, both of which suck: either they will never get to smoke again, or they will and will have failed.

To avoid the latter, they adopt positions designed to realize the former: cultivated disgust, deferred commitment, and honest, foreclosed desire:

In the first, passing by another smoker on the street, they think, “What an idiot! Who would do this to themself?” With enough concentration, they reach a state where the same smell that used to tempt them now makes them retch and they’ll be unable to stand outside of bars.

The second, after a few failed rounds of quitting, requires pretending they are making no attempt at all. When they do not admit they’re trying to quit for good—instead taking only a week, or a month, or a year off, perhaps even just to prove that they’d be hypothetically capable of a longer-term break, had they the desire to test themself further—they can avoid other’s disappointments when they pick the habit back up.

The final is my favorite since it’s the truest. Instead of becoming disgusted or putting off commitment, they treat cigarettes the same way they’d treat crushes while in monogamous relationships: something they want but have promised to resist. As with sexual commitment, they take responsibility for avoiding the scenarios that make breaking this promise more likely, like alcohol, stress, solitude, or anything that makes their temptation easier to give into.

While any of these poses might work, they give the cigarette too much power. The real goal, I imagine, is to categorize cigarettes with the magic talismans of childhood—stuffed bunnies, soiled blankets, pacifiers, lullabies, memorized books, baggies of Cheerios, even parts of the child’s own body, like thumbs or cheeks—these things that once caused us to weep when they were taken from our little hands, to beat the ground, to swear we could not go on living without them. Cigarettes, like Al and Betty and Space Panda and Easter, should somehow become secular.

Diana Hamilton is a writer, poet, and the author of three books: God Was Right (Ugly Duckling Presse), The Awful Truth (Golias Books), and Okay, Okay (Truck Books). She received her PhD in Comparative Literature from Cornell University. She lives in New York.