On White Jeans

Loose threads unravel. A pair of shoes is maimed by concrete. A seam comes loose on a woolen sweater. The torn knee of a heavily worn pair of jeans, even if patched up, still draws attention to the old breakage. A pocket frays through overuse. Age gives life to a garment that was once pristine and inhospitable, that we once treated with delicate and feared reverence. Black, in the warmth and wetness of a washing machine, slowly turns to grey.

Fashion is designed with transience in mind. It is made to be used and worn. Use leads to material degradation. Time means it will, eventually, as everything does, go out of fashion. Although of course, some things come back around, become fashionable again.

Often you will find very expensive minimalist clothing marketed as timeless. As if it was possible, somehow, to create above the swelling waves of trends. As if minimalism is not an extremist position and timelessness is not a chimerical impossibility. Everything starts and everything ends. We cannot escape the context we create in: an item of timeless luxury created today looks different from an item of timeless luxury created yesterday.

A garment degrades with wear, with changing tastes, with the changing shapes of a body as it progresses through life. That slinky Duran Duran crop top you wore at seventeen, full of juvenile thinness, would be ridiculous today. And some clothes require the heavy gravity of age to wear and some demand the opposite; only working on a body crafted in perfect confident naivety.

The demands we place upon an item of clothing change too. A once fashionable T-shirt, now half-decayed by overuse and changing trends, can be worn to repaint the downstairs bathroom without worry of ruining it. Equally, a T-shirt distressed and sun-bleached, its deepest blues faded to dark shades of oranges and yellows, gains a new aura of authenticity, becomes cool. And clothes bought and worn and then discarded to the back of the cupboard, over an interval of time and unuse, develop a sense of newness again, live second lives.

I bought my first pair of white jeans from eBay eleven years ago. I was at my grandparents house, sitting on the kind of sofa you only find in the homes of grandparents, browsing eBay. They were probably about fifty pounds. Newish. Ralph Lauren. Skinny with a hint of flare. A little too big in the waist. But such are the perils of eBay purchases. I had never worn white jeans until this moment in time.

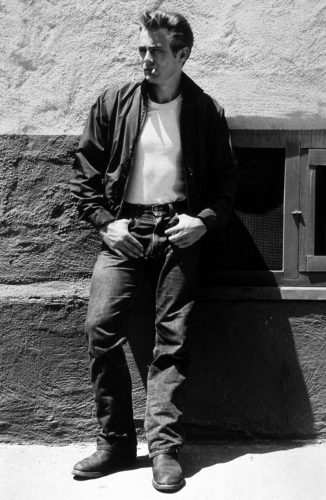

I was probably inspired by David Hemmings in Antonioni’s Blow Up, which I had probably just seen for the first time. He spends the film wearing white jeans, a blue shirt, a dark blazer, black boots, a wide, black belt. His hair is perfect, off-blonde, expansive. He is pallid, sensitive, troubled, creative; he is the way all young men want to see themselves. But there’s some alchemy in this outfit, presented this way by Antonioni, this mix of danger and sophistication and sex. Those pristine white jeans in the hazy, crumbling, swinging decay of ’60s London. I wanted to look like David Hemmings in Blow-Up. And more than just looking like David Hemmings in Blow-Up, I wanted to feel like him.

Putting on a new item of clothing can turn you into a new person. Clothing contains the existential magic of realization. This is the obvious promise of a thousand TV makeover shows and the more oblique promise of advertising, the fashion industry in general, the influencers we follow on Instagram, and all the various forms of art we consume. All desire is a type of transformation. A suit can turn you into a businessman, a pair of leather trousers can turn you into a rock star. Dreaming of the ownership of an item of clothing, spurred by a film we saw or an image that flashes up through the scroll of our phones, turns us to dreaming of a more complete, better, cooler, sexier version of ourselves even if it is impossible to truly leave ourselves behind. It’s hard, painful work to become who you aren’t and to maintain that pose. Fashion can give you the superficial allure, for a moment, of being someone you are not, in the same way you are a version of yourself in a dream.

I still have that pair of white jeans I bought eleven years ago. I have supplanted it with a dozen other pairs of white jeans in various materials and cuts, from various brands, in shades of white, cream, beige. I love the easiness of them. They go with anything. I love the vague patina of use that clings to their perfect whiteness; small flecks of dirt and pollution and existence that disappear in the wash. White jeans, generally, wear their marks well; they exude life, tell tales of clumsiness, use, negligence, flecked with the light grey ash of a cigarette, a hint of red sauce from a burger eaten quickly on the go, the red brick of a wall sat upon, a droplet of Guinness from a badly carried pint, a dribble of coffee clumsily drunk. The knees slightly misshapen from sitting down all day in an office and the outline of a wallet and phone pulled into the shapes of pockets.

The blankness of white jeans lends itself to poetry. The blankness of white jeans lends itself a certain timelessness I claimed was impossible earlier, in the same way a pair of blue jeans has an eternality to it. Or a leather jacket. A white T-shirt. They are more than their individual, specific garments, but they become something bigger and less material, which is to say they become mythologies.

The individual garments you may own and wear are much more materially specific, much less rooted, their meanings shift quickly. Everything we wear is a statement. With some cultural context you can pull in any meaning you desire. A band T-shirt carries the weight of the band’s entire output or it is just a cool T-shirt. Blue jeans and a white T-shirt could label you a Bruce Springsteen fan or just someone wearing blue jeans and a white T-shirt. Five years ago my Vetements T-shirt proposed a certain insideryness, a knowledge of fashion’s systems of value and irony. Now it would mark you out, in certain contexts, as passé. Or if you are having lunch with your mum, who knows nothing about Vetements, it’s merely a T-shirt you own. And then tomorrow, that same Vetements T-shirt, worn again, in another context, will gain an air of rebelliousness, a disregard for fashion’s systems of irony and value, known and acknowledged and discarded. In America they say you shouldn’t wear white after Labor Day. Luckily, not living in America, this rule doesn’t apply to me. It’s nice to know about the fashion rules one is ignoring. There is pleasure in disregarding them.

Most of the clothes we wear have more prosaic attachments, are worn much lighter and with less thought. Sometimes a T-shirt is just a T-shirt and some clothes hold no memories and no conceptual weight beyond our own personal histories. There is not much left to be said about the ritualistic attachments of the suit, creased and ill-fitting, pulled out from the cupboard a few times a year for various weddings, funerals, christenings. The deeper attachments are subtler, more powerful, they drag us down into the fullness of memories: A cheap tourist T-shirt bought on a family vacation; a sweater that belonged to an ex and was surreptitiously stolen; grandad’s old scarf passed down after he died; a pair of opera gloves that belonged to your mother.

Jewellery has a more physical immortality to it, it’s designed to continue to exist, and so, even before being handed down, it has an innate sense of the heirloom around it. The material precarity of the garment, especially the garment that is worn and loved, lends a temporal sadness.

I bought those white jeans while sitting on my grandparents’ sofa. I’ve worn them constantly since. For a long time my girlfriend’s phone background was a picture of my leg, in those jeans, with a black loafer on my foot against the cold tiled floor of Gallerie Emannuel II in Milan. I would not have expected this when buying these jeans at that time. But then why would I?

I spent much of my life in my grandparents’ living room. I can recall it perfectly. The wood panelling, the old green-blue sofas, the old TV, the heavy smell of pipe smoke and strongly brewed tea, the fragrance of Earl Grey, a dictionary so ancient it didn’t have the word “television” in it. The dim lights. The fireplace. The heavy iron grate and tiling. The years pass and grandparents become increasingly rooted to their chairs. Life gets more exhausting and you spend more time sleeping. The eternal background noise of the TV news. A cryptic crossword filled in almost automatically.

I remember, just after I started working full time, I was living in London and went home for Christmas. I bought my Granddad a nice, too-expensive cardigan. All his old cardigans were mottled with holes from pipe ash. My grandma wouldn’t let him wear this too-expensive cardigan because the cardigans he already owned still had use. And, anyway, it was too nice to wear. And after they were both dead and we were cleaning out their house, the cardigan was still there, barely worn.

Felix Petty is the Executive Editor at i-D. He is based in London.