I first met Matthew on February 22, 2020, at 10:30PM. I’m certain of the date and hour because of a text message from the “underground” film director Damon Packard that’s still on my phone. A month earlier I had read, online, Matthew’s profile of Damon, which captured him perfectly, down to the broken transmission in his car and the detritus piled in its passenger seat. I praised the profile to Damon, and he must have relayed my praise to Matthew, who wanted to get together I was told. A meeting was arranged at a diner in Los Feliz, House of Pies, where I had often met Damon for late-night snacks or meals, and when others joined us at his invitation, he tended to disengage, staring at his phone, and leave the conversation to me. It wasn’t a problem if the others were effusive, but Matthew seemed reticent, or he did initially, so that I dreaded having to draw him out while Damon texted and googled and scrolled through Facebook. I knew already that Matthew was Australian—he had written as much in his profile of Damon—but he was younger than I expected, and I could tell he was tall before I’d seen him on his feet.

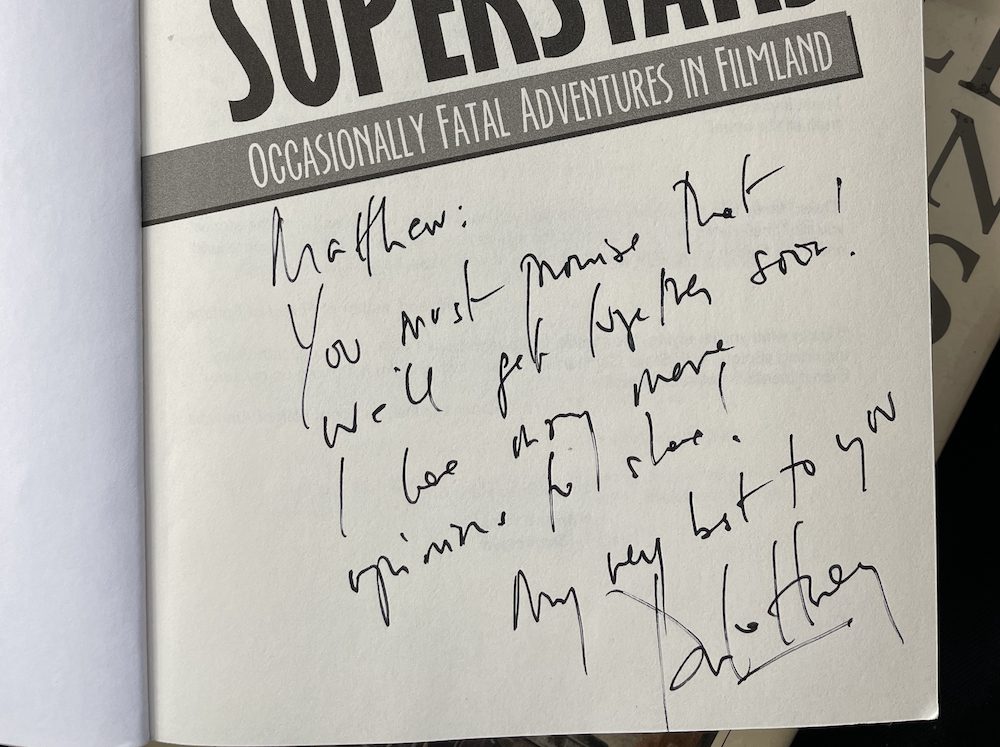

But I couldn’t tell why his skin was red and scabby. I couldn’t bring myself to ask why, but then Damon asked in his obtuse way and Matthew explained it as a side effect of chemotherapy. He had cancer, he said almost dismissively, as if it were a subject he wished to avoid, not because it was painful or private, but because it interfered with subjects of years-long interest to him. He and I had more in common than Damon, I learned now. He was a connoisseur of what I’ll call psychedelic noir, trippy true stories of the kind peculiar to Los Angeles; and I had written a book full of such stories, Death Valley Superstars: Occasionally Fatal Adventures in Filmland, and happened to have a copy in my car, so I fetched it and inscribed it and gave it to Matthew. He mentioned another book of the psychedelic-noir sort, one he had read recently, Swim Through the Darkness, about Craig Smith, an obscure singer-songwriter and native Angeleno who lost his mind while traveling abroad in 1968 and returned home a disheveled would-be messiah: Manson minus the homicidal harem. “That sounds right up my alley,” I said, though I found it odd that an author would devote an entire book to a person of no repute. Matthew and I exchanged phone numbers, and a day or so later I ordered a copy of Swim Through the Darkness. It might be useful for research, I thought, since I was trying to write a novel that was set in L.A. in the ’60s and ’70s.

But Swim Through the Darkness proved to be more than mere research. I read it, gripped and wrenched, in a couple of days and texted Matthew to thank him for alerting me to it. That message too is still on my phone. It was sent on March 3, and Matthew answered within minutes: “I was actually going to text you today, just on the last few pages of your book!” He cited the section on Sean Flynn as his favorite. Sean Flynn is, or was, the tragic son of Errol Flynn, Tasmania’s most famous native, and Matthew “partially grew up in Tasmania,” he texted me. He texted me about the mystical artist Marjorie Cameron and her husband, the pioneer rocket scientist Jack Parsons, who both figured peripherally in my embryonic novel. He texted me about The eXile, an iconoclastic newspaper that was published in Moscow from 1997 to 2008 by an erstwhile friend of mine, Mark Ames. Back and forth the messages flew that day: I count a hundred and sixty-five of them. “Gotta put the baby down now,” Matthew texted me finally, “but we should get a coffee soon if you’re around.”

So, four days later at eleven AM, we met for coffee in Los Feliz, this time at the Alcove Café. The Alcove was my suggestion. The building had once been the recruitment center for the Unification Church founded by the Reverend Sun Myung Moon, whose adherents came to be called Moonies, and I thought Matthew would appreciate the disconnect between the overpriced bistro of now and the zombie factory of yore. It was an overcast morning and a bit chilly, but we sat outside on the patio, and though I don’t remember any specifics of the conversation, probably I harangued Matthew with the plot of the novel I was struggling to begin. What I do remember is a look of fondness in Matthew’s eyes, and fondness is not a word I apply typically to my interactions with men. Already, it seemed, we were great friends in the way that children become great friends at expedited speed. He never told me explicitly that his illness was terminal, and if it was terminal, hopefully we could continue to meet as often as his condition and schedule permitted. He was, after all, a new family man. Cancer, be not proud.

But it was COVID-19, not cancer, that prohibited future meetings. Because of COVID, a statewide stay-at-home order took effect on March 19, though its impact on me was negligible, or as I texted Matthew on March 23: “I’m like Proust almost, except without the cork-lined room and servants.” It was similar for Matthew, he texted back: “Obviously I’m being more cautious than most but life hasn’t been disrupted too much.” Hospitals were reportedly overwhelmed with COVID patients and I was concerned that Matthew’s treatment would suffer as a consequence. “[I]f you’re ever in need of an ear or distraction, please don’t hesitate; I’m at your disposal,” I messaged him in April after he posted on Instagram about disappointing scan results and a new chemotherapy regimen. He updated me about the new regimen in May: “[I]t’s not bad at first but it completely wipes me out for the second half of the week unfortunately—like falling asleep at 2PM. Hopefully my body starts to get used to it and I can tolerate it more. How are things with you?”

“I’m not going to complain,” I replied. “How can I when you don’t?”

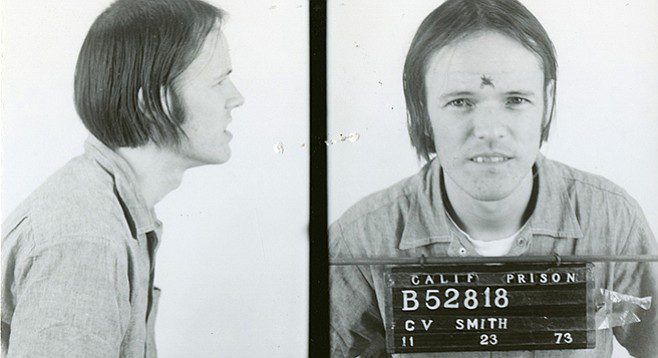

I might have complained, writer to writer, if Matthew had been healthy: my novel was going nowhere, despite months of daily labor. In June I discarded my latest dead-end beginning, and one afternoon, seeking inspiration, I watched a widely forgotten movie from 1969, a drama with a lot of location footage of L.A., Hollywood especially. I chanced upon the movie on YouTube, and while the script was weak and the direction was mediocre, I was struck by the performance of the lead actor, who played a Vietnam War veteran with post-traumatic stress disorder. I googled him and learned he was a Vietnam vet in reality. He had also been a rock & roll singer. Then he switched to acting and starred in four movies, including a minor classic, which premiered around the time he died in a plane crash in 1973. That was as much as Google had to say about him, so I dug through newspaper archives and discovered that the plane crashed in Texas in the course of marijuana trafficking and the actor’s remains were buried locally in potter’s field. What a life! What a story! Yet it was barely reported in 1973 and no writer had touched it since. I wished I had been aware of it when I was working on Death Valley Superstars: it would have fit that book perfectly. Now I had a novel to write.

But the novel could wait, I decided. If I didn’t pursue this story, nobody would, and those with memories of the actor, his surviving friends and relatives, would all be elderly, so that I should try to track them down without delay. I was too late in some cases, but I spoke to an astonishing variety of people, cold-calling them at numbers I found on the internet, meanwhile requesting documents from this and that government agency. I wasn’t sure what I would do with the story when I had collected enough material to write it, but I knew it wasn’t a book. The actor didn’t warrant a book. He was a footnote—a fascinating footnote to me, of course, but I did not intend to waste years on a book with a readership of the author exclusively.

Somewhere in mid- or late June, COVID restrictions were eased somewhat, so that I was able to meet Damon Packard at House of Pies one night. “It was rather strange,” I texted Matthew, “to sit in a restaurant, however empty, after months when I never went near one. It was like acquiring a new skill, almost.” Matthew answered that he had been in the hospital “with a blocked bile duct. Took a while to recover from the jaundice etc. [F]eeling much better now. Have to see how the ‘opening up’ goes but we should catch up for a coffee again.” Had we done that, I would certainly have led him through the actor’s story. I would also have mentioned that, via Facebook, I was now friendly with Mike Stax, the author of Swim Through the Darkness. Mike understood my fascination with the actor’s story very well and arranged for me to interview a particularly helpful source, the actor’s former neighbor in Hollywood. Mike and the former neighbor had a mutual acquaintance.

On July 28, Matthew posted an update on Instagram. His latest scan was “what the doctor calls ‘stable,’” he wrote, which was “better than we expected given some of my recent symptoms. It has been a hard few months. We have been waiting for this scan to make a decision about relocating to Sydney to be near my family. When we asked my doctor, he recommended that we do it ‘ASAP’ while I am feeling relatively normal. It looks like we will be moving sometime in September. This was a tough decision as we were building a beautiful life here pre-Covid/diagnosis. We also have many people in L.A. that we love dearly and it’s tough to leave them behind. L.A. is an odd place, but over the last five years I’ve learned to love its dirty streets, raw beauty, and its bizarre history and mythology.”

Rather than comment publicly on his post, I texted Matthew on July 29: “Sorry to hear you’re moving, yet happy at the same time. And of course glad to hear about latest results.” He didn’t respond, so I texted him again two days later: “I hope to speak with you before you leave; I know seeing you is out of the question.” This time he answered: “Sure thing. Sorry for the delay—I got admitted to the hospital with a fever. They thought it was Covid but it’s actually just a bacterial infection. I’ll be in the hospital for a few days, but we should definitely chat when I get out.”

But we didn’t chat when he got out. Maybe we would have chatted if I had pressed him, but who was I to press him? I had known him for all of five months. Even so, wanting to hear he was reasonably okay, I texted him on August 18—“What’s going on?”—and he texted back a few hours later: “Hey Duke, been in and out of the ER a few times since we spoke but back home now recovering. They just couldn’t get rid of an infection I had but eventually got it under control. Not feeling that great so it may postpone the move—along with a couple of other issues. How are things with you?”

Those were his final words to me—“How are things with you?”—and these are my final words to him: “I can’t complain—certainly not to you, my friend. Are you up to a chat on the phone?”

I’m glad he didn’t respond: I would hate to think I stole even a few minutes from his wife and child. I had stolen too many of his minutes already. He read my book, for God’s sake! From the countless books published over the centuries, he elected to read mine while his time was running out. I hoped it wouldn’t run out completely before he moved to Sydney. I kept an eye on his Instagram account for news of the move, but it never came.

Instead he posted photos that amounted, I thought, to a life review. Here he was as an infant with his father, a redhead like Matthew. Here he was, still an infant, at his grandparents’ house in Miranda; and here he was, an adult now, pouring wine in his apartment in St. Kilda; and here he was in the foyer of a hotel in Hollywood with his wife, Rebekah, who was two months pregnant with their son, Micah. I recognized the hotel: my actor-marijuana trafficker-rock & roll singer-Green Beret lived a few blocks north of it. Yes, he wasn’t just a Vietnam vet, he was a Green Beret, I had learned. Every day I seemed to wake to a revelation about him.

Then one day—it was October 19—there was a revelation about Matthew: he had died the previous morning, Rebekah announced on Instagram. The announcement was accompanied by a photo that Matthew had asked Rebekah to share. It was a family photo: father, mother, and child sitting at a table in a sunny room. The father’s illness was conspicuous. I was crushed. What could I do? What could I say and to whom? Matthew and I had no mutual friends aside from Tosh Berman and Damon, and I didn’t know Tosh well and I would never turn to Damon for consolation.

But I wanted to mark Matthew’s passing somehow, and stupidly, I did so on Facebook. Election Day was on the horizon and Facebook was a hotbed of partisan sparring, so by posting about Matthew there, I meant to provide some needed perspective. The gist of my post went something like this: “Let’s all stop bickering and consider what really matters. It matters that this gentle, intelligent, promising person is gone too soon—and please don’t offer me condolences. They belong to his family, not me.”

I got a lot of condolences. They made me feel worse, not better, as if I had used Matthew’s death to solicit sympathy for myself. I left a comment on Instagram for Rebekah to read and submerged myself in the actor’s story. The revelations continued. I learned that the actor’s grave in Texas was temporary, that his remains were exhumed at the behest of a priest, evidently a childhood friend, and moved to a cemetery in Illinois, where the priest was buried alongside the actor fifteen years later. Not even the actor’s family knew he was buried in Illinois; I found his grave after much internet sleuthing. I found his closest friend in Vietnam, a fellow Green Beret who was now a grizzly-bear expert living in Montana. I found the kingpin of the marijuana-trafficking ring, who had children by three sisters and once escaped from federal prison by hiding inside a speaker cabinet following a rock concert performed for the inmates—“the best concert I ever saw,” the kingpin chuckled to me.

How could there not be a book in all this? No, the actor wasn’t famous, but neither was the singer-songwriter of Swim Through the Darkness, and if Mike Stax wasn’t deterred by his subject’s obscurity, why should I be deterred by mine? A good story is a good story, as Matthew was bound to have agreed. It was Matthew, after all, who introduced me to Swim Through the Darkness, which inspired me to investigate the actor’s story. I think I was looking for such a story from the minute I finished reading Mike’s book, though it was months before I realized as much.

Now it’s a few days shy of a year since Matthew died, and my book is not yet a book. More research is required, and some of it will have to wait until COVID restrictions have lifted entirely. Here and there, I work on my novel, still trying to crack the beginning. Matthew seemed genuinely interested in the novel when I told him about it at House of Pies, and that alone is incentive for me to keep at it. The time I spent with Matthew was brief, obviously—it may have come to four hours, discounting the day we exchanged a hundred and sixty-five text messages—but time isn’t always an accurate measurement of impact. A life can change in an instant because of a stranger, or in this case, a sadly fleeting friend who bequeathed me a book by referring me to another one.

Duke Haney, also known by the pen names Daryl Haney and D. R. Haney, is an American actor, screenwriter, novelist, and essayist. His books include Banned for Life (2009), Subversia (2010), and Death Valley Superstars: Occasionally Fatal Adventures in Filmland (2018). He lives in Los Angeles.