Circling the Arrow

The following essay was commissioned and written in 2014 for a collection of writing on technology and surveillance.

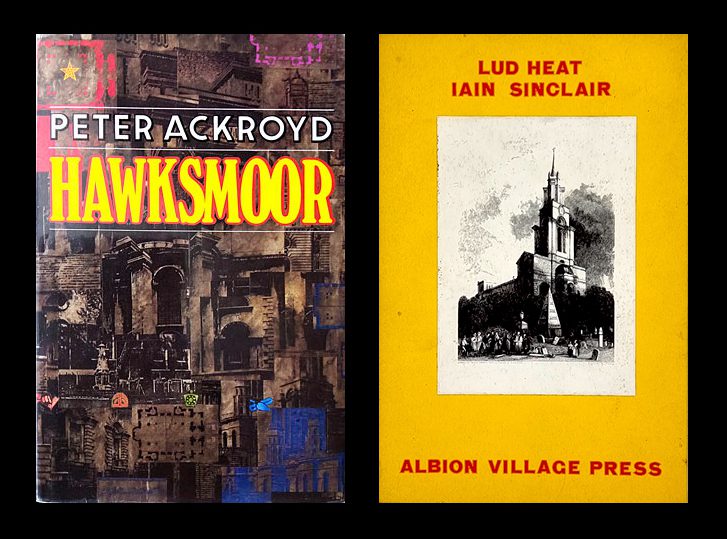

“Is he the arrow or the circle?” As the two friends looked at their screen in an attempt to locate a third, traversing another continent, I glanced at my own phone. The grid of London streets appeared; it took me a second to find a small blue sign, a circle with an arrow next, but not quite attached, to it: that was me, sitting in a café, facing east. Putting the phone away, I thought of another arrow, drawn by Peter Ackroyd in Hawksmoor, where two Londons are juxtaposed in time. The novel, first published in 1985, was inspired by Lud Heat, a book written by Iain Sinclair a decade earlier.

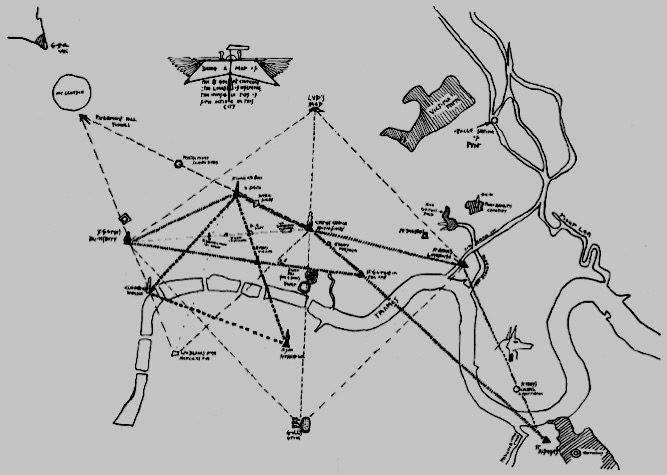

Moving across London, Sinclair sketches a complicated figure in his work: “A triangle is formed between Christ Church, St George-in-the East and St Anne, Limehouse… St George, Bloomsbury, and St Alfege, Greenwich, make up the major pentacle-star.”1 More lines are drawn to add St Luke’s obelisk and St Mary Woolnoth to the picture. In Ackroyd’s book the figure is simplified: “Four crosses… three of them in a triangular relation to each other and with the fourth slightly apart, so that the whole device resembled an arrow.”2

The churches Sinclair and Ackroyd use as apexes were built by Nicholas Hawksmoor after the Great Fire of London. “From what is known of Hawksmoor it is possible to imagine that he did work a code into the buildings, knowingly or unknowingly, templates of meaning, bands of continuing ritual,” writes Sinclair.3 “His motives remain opaque; his churches are the mediums, filled with the dust of wooden voices.”4 One page in Lud Heat is filled with a poem shaped like a down-pointing arrow.

I remembered the arrow-shaped poem a few days after the conversation in the café, walking in London by myself. I thought of stopping for a coffee at a stall just outside Christ Church Spitalfields, a magnificent 18th century building, one of Hawksmoor’s six London churches. The poem warned: “Too much melodrama, churchyard lunches. Picnic against the pyramid at your risk.”5

I took the risk knowing how good their coffee was. Drinking it by the railings, I compared the two authors: Sinclair, who was largely responsible for the popularity of psychogeography in Britain (although he has never claimed to have initiated its revival), and Ackroyd, who probably was also similarly accountable (although he has always dismissed the very term as irrelevant). When I recently approached Sinclair for an interview, he told me: “I feel talked out on the topic of psychogeography.”6

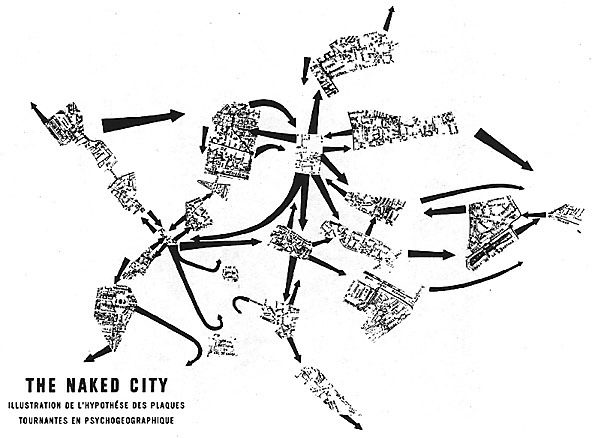

Is psychogeography still relevant? If so, should it be considered a private or collective practice now that privacy is something we can no longer afford? Back in 1956, setting the scene for Situationist activities, Guy Debord recommended that the dérive, one of the key psychogeographical pursuits, should be conducted individually or in small groups. His best known work, The Society of the Spectacle, an examination of capitalist consumption published in 1967, barely mentioned psychogeography; two decades later, analyzing the way the spectacle had spread, he talked of people conspiring in favor of an established order: “From the networks of promotion/control one slides imperceptibly into networks of surveillance/disinformation.”7

However, the omnipresence of these networks today does not seem to undermine Debord’s early definition, “Psychogeography sets for itself the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, whether consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals. The charmingly vague adjective psychogeographical can be applied to the findings arrived at by this type of investigation, to their influence on human feelings, and more generally to any situation or conduct that seems to reflect the same spirit of discovery.”8 I was willing to take the qualifier “charmingly vague” as encouragement for my subsequent excursion.

Still, what’s the point of psychogeography in the smartphone era? The practice involves recording anything and everything as you wander around. Looking at my phone, I wondered if it was still possible for a 21st-century flâneur to record anything new. Apparently, everything has already been digitized. And if mass surveillance is a fact of our everyday lives now, how does it fit in with the society of the spectacle? Now that information in its every guise has become the main component of our existence, which side of disinformation does the psychogeographer find themself on? I would have to undertake a dérive before I could try to answer these questions—but the idea of a dérive with a phone in hand seemed oxymoronic, even in light of the Situationist call “to avail ourselves of all the new technological inventions.”9 My thoughts went back to the arrow and circle, their closeness another proof of the fact that the observer and the observed are one.

In December 2012, when Google Maps was first offered as a free mobile app, the Guardian commented: “As ever with free services, users aren’t the customers, but rather simply a commodity.”10 GCHQ and the NSA were said to be planning to put every mobile phone mast in the world on the map—that is, in their database (another way to locate smartphone users would be to intercept Google Maps queries). As a 2008 report by the British intelligence agency claimed, “anyone using Google Maps on a smartphone is working in support of a GCHQ system.” Curious to find out more, I asked a tech-savvy colleague to tell me about the latest developments. (He didn’t know what psychogeography was; in fact, most people I talked to didn’t, although when I explained the concept, they would say: “But of course.” One acquaintance told me of a device he’d built, a sensor measuring galvanic skin response, used in what is known as emotion mapping). The latest from the techie, if I understood it correctly, was this: you can trick whoever is watching you by running a special software, so they think you’re marlin fishing in Kingston, Jamaica, while you’re drug dealing in Kingston upon Thames. However, you can’t do it dynamically—that is, you can’t superimpose your perambulations onto a map of a place where you are pretending to be.

As I write this, someone is probably working on new anti-spy software. Do they know about the Situationist practice of using a wrong map? Debord posits it in a 1955 piece: “The production of psychogeographical maps, or even the introduction of alterations such as more or less arbitrarily transposing maps of two different regions, can contribute to clarifying certain wanderings that express not subordination to randomness but total insubordination to habitual influences (influences generally categorized as tourism, that popular drug as repugnant as sports or buying on credit).”11 Last summer, on holiday in East Anglia, my companion and I wanted to visit Framingham Earl, a Norfolk village where W.G. Sebald is buried. On hearing of our plans, our host gave us a pocket map. When we got there, we tried using the map, which bore little resemblance to the surroundings, until we noticed that it was, in fact, a map of Framlingham, a market town in Suffolk. Eventually we found an old church and spent a long time in the graveyard looking for Sebald’s grave. We went up and down every row, with no luck. There was no 3G coverage, so our phones proved useless. Thinking it might still be the wrong Framingham Earl, we left. Back online, we discovered that it was the right place, after all, and looked at the photos of a grey tombstone inscribed with:

We didn’t return to the graveyard.

Walking in London again, contemplating cartography, I have an idea: type into Google Maps whatever I’m looking for and see what suggestions come up. Strictly speaking, it won’t be psychogeography—you’re not supposed to look for things specifically. Psychogooglography, as it were. On the other hand, it might just qualify: there is a certain degree of randomness to the process. Apart from a number of paid listings, Google seems to be picking venues without much method. Touching the screen might prove as arbitrary as turning a corner.

A few weeks earlier, I was in Wapping, East London, on a pub terrace overlooking the Thames, the skyscrapers of Canary Wharf looming over old warehouses. The cityscape put me in mind of an interview with Ackroyd five years previously, when he, asked about the best place to start exploring London, said, “Wapping.”12 A man with an iPhone came out on the terrace announcing that finding the pub was easy with Google Maps. He looked like he was more likely to have a compass on him, perhaps even a crystal ball. A former psychogeographer gone hi-tech? He told me about his poetry collection, out soon, and encouraged me to contribute to a magazine he edited, something topical on gender issues. I never got in touch.

Practitioners of psychogeography, no matter what their school, usually wander around and record whatever they come across. Perhaps Google Maps could be utilized to find out what’s already recorded and thus to aptly survey the current historical and economic moment: who’s interested in what, who’s paying whom and why? Hawksmoor’s churches are already there, marked on the map by some enthusiast, blue drops speckling London. Church of Little St Hugh is there too, despite existing in Ackroyd’s book only. The chapters of Hawksmoor alternate between the early 18th century and the 1980s, the former written in the language of the epoch. The Hawksmoor of the title is a Met Police detective investigating a number of murders in the capital. The other protagonist, the architect Nick Dyer, consecrates his London churches with human sacrifices; Little St Hugh, his magnum opus, rises in Black Step Lane (also fictional), once the site of a satanic cult. As I study the map, my idea gains momentum, developing into something more concrete: I’ll consult my phone for whatever tips it can offer and follow in the footsteps of both Dyer and Hawksmoor—whose last walks, separated in time but coincident in space, bring them to the imaginary church. I won’t save any of my searches to make sure I get information straight from Google’s mouth. I know this part of London well, so don’t need any directions; I know where the church is meant to be; I will come up with search phrases as I go.

At the time of my dérive, reports about anonymous location data collected by Google kept appearing in the media, yet I couldn’t care less about software companies responding to whatever user information requests about me they might get. Messages from Twitter explaining how they collect certain types of information, including locational coordinates, and record personal data when a new application is installed, didn’t bother me; I could see no reason why I wouldn’t be able to use technology rather than be used by it.

Once, at an event called “Don’t Spy on Us,” I asked a web security specialist about protecting personal emails; he told me: “If it’s web-based, forget it.” So I do, before setting out for a walk, intent on playing the role of the observer, not the observed. My aim is not to reclaim the streets, Situationist-style, but to plot my own arrow and circle onto the “overgoogled” grid.

Sunday: mid-morning, a popular flower market in Columbia Road, East London. Approaching the area, I take out my phone to consult Google Maps. The first attempt is not overly encouraging as I type in:

Onto the market, where “chronological resonances” (Ackroyd’s term and subject) abound. A trader in a Hawaiian shirt, a massive cross dangling from a golden chain round his neck, yells: “Eighteen mixed winter pansy a fiver!” Another stops mid-chant, slows down to talk to a foreigner dawdling at her stall: “When it dies, you cut. Cut ‘ere. Yeah? Good—you understand.” Music, live and recorded; a young man humming, tapping his foot, looking at an old guitar player approvingly. Styles and periods piling up one on top of another.

I’m not far from Christ Church, and wonder if the coffee stall is open on Sundays. It is, but I have no money, so search for:

Cash →

Royal London Cash Management; Prince Cash & Carry

Cash machine→

Barclays Bank Plc; ATM; NatWest Cash Machine

The nearest of the last three results is 5.7 miles away; the farthest, 14 miles away. Further down the list, I find a cash-point right across the road, the one I’m already heading for, marked 0.8 mi, closed. No, Google, you are not ready to conquer this city yet. There is a long queue for the cash machine (does the app know? does it take live data into account to optimize search results?). While waiting, I look up:

Coffee→

International Coffee Organization

Coffee shop →

Workshop Coffee ● Independent roasters with all-day menu

Coffee shops→

The Ritz London ● Glitzy hotel famous for afternoon tea

The distances to these establishments are between 1.2 and 3 miles; the stall is yards away from me. I am reminded of the theory of “disinformation” according to Debord, as well as of Michel de Certeau’s claim that “[b]eneath the fabricating and universal writing of technology, opaque and stubborn places remain.”13

In the queue, a group of Italian girls chatting away, not on their mobiles—to each other. Finally, cash: £20 and £50 notes only. I get £20, which could buy me seventy-two mixed winter pansy plants, and cross the road. The stall serves coffee in the best paper cups in town, but they have proper ones too: straight black-and-white china cylinders, curved glasses with metal handles. I get an espresso and sit at a table, leaning against the off-white stone, a notice next to my shoulder advising disabled visitors to press a button or call a number to gain access to the church. I have another go at my phone, inputting:

Church →

Temple Church ● Iconic literary 12th-century church

Fenchurch Street. Walking past the Walkie-Talkie building, two ropes stretched along its smooth expanse of glass, knots at their ends appearing particularly out of time. A man hurrying by sees me stare at the ropes, takes out his phone and snaps the skyscraper. Nearby, a Vodafone store, its window telling urbi et orbi to “Enjoy London with a 4G network you can depend on” (note the wording: “depend” rather than “rely”).

I realize I need to be more specific with my queries. Black Step Lane, the site of Hawksmoor’s Little St Hugh, might get me closer to the point, so I query Google Maps for:

Black Step Lane→

45 Park Lane ● Intimate luxe hotel with Hyde Park views; Aladin Brick Lane ● Small, long-standing curry house

And then I enter:

Little St Hugh →

Clarence House ● Royal palace with formal gardens & tours; Nightjar ● Prohibition-style speakeasy bar, closed;

Hugh F Shaw & Co ● Estate agents;

LSO St Luke’s ● Symphony orchestra’s music centre

A Hawksmoor connection at last: the tower of St Luke’s, over in Old Street, is his design. Onto St Mary Axe, where two children in front of the Inside-Out building are counting its floors, their father brandishing an expensive-looking camera. Photos are not what I’m after. Once again, I try:

Church →

Saint Olave Church of England ● Medieval chapel & burial place of Pepys; St Bartholomew the Great ● 12th-century church with cloister cafe, closed; St Andrew Undershaft ● Historic CofE church amid modern offices.

According to the app, St Andrew Undershaft is 144 feet away, although I’m right by its gate. Is that counting from the altar? Can’t be—the church is tiny. More disinformation, perhaps. A “Google User” gives it ★★★★★. The Gherkin appears in my view, looking so cozy surrounded by bulkier, edgier buildings, the only startling thing about it being my own reflection in the dark panels. A few steps down the road, the Gherkin again, reflected in its neighbor. A dull piece of sculpture, “presented as part the City of London’s Cultural Strategy [sic].” According to the program organizers, “The onstreet delights of ‘Sculpture in the City’ will give Londoners and visitors a chance to see the Square Mile from a whole new thought-provoking perspective over the year.” Sinclair’s recent LRB piece springs to mind, where, walking in a soon-to-be-gentrified part of London, he winces at developers’ ads written in a “language… so twisted, doubled back to mean its opposite.”14

Wormwood Street in the shadow of Heron Tower, topped with SushiSamba, a “destination restaurant and sky bar.” London Wall. The offices of Deutsche Bank, equipped with CCTV, security men bored inside, perhaps watching the uneventful footage. Abstract pictures in the lobby, a plasma screen promising “ArtStation.” Debord, again: “While all the technical forces of capitalism contribute toward various forms of separation, urbanism provides the material foundation for those forces and prepares the ground for their deployment. It is the very technology of separation.”15

Across the road, a stretch of the wall, moss-covered, with a plaque reading “W A H 1888.” Closed cafés: coffee revolution suspended in the City on Sunday. On my left, Throgmorton Avenue: a locked gate with three compasses and the motto “Honour God” on it. Two Polish builders passing, talking on their mobiles—are these the new Freemasons? A plane overtaking a helicopter above.

I was once stopped at London Wall by the police. We were filming a series about British literature: I was driving, the cameraman was making cutaways. As we observed the area (while also, it turned out, observing the law), the police followed us, observing the camera sticking out of the car window. They asked to see our press cards, took down my number plate and wished us a good afternoon. The interview with Ackroyd, part of that series, took place the same week. Talking about ways to understand London, he said: “It’s a question of sympathy rather than observation, of intuition rather than knowledge.”16

I turn off London Wall, enter Moorfields, a small street tucked behind Moorgate tube station, the Great Field adjacent to Black Step Lane in Ackroyd’s story, and enquire about:

Moorfields→

Moorfields Eye Hospital ● Hospital, closed

Has it fallen victim to the recent austerity cuts? On the way back, I stop by the hospital to make sure that come Monday morning, it’ll be business as usual.

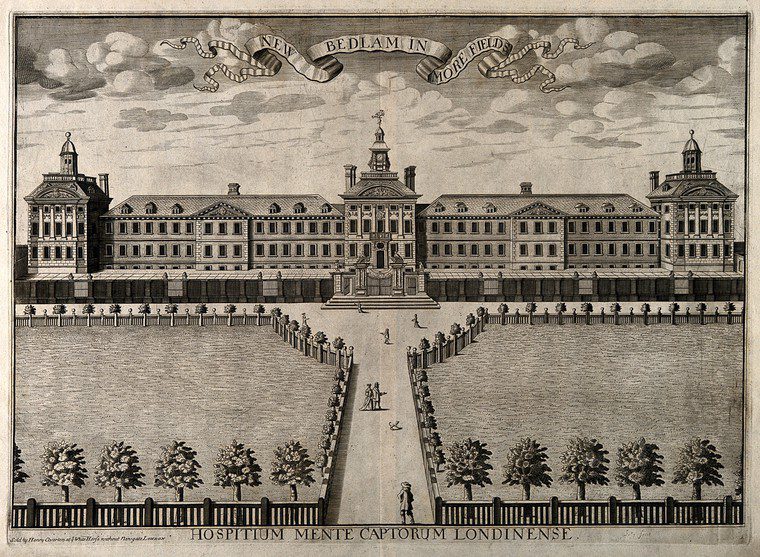

Where Bedlam, or the Bethlem Royal Hospital once stood, a lame woman now walks in the road toward the dark hulk of the British Red Cross HQ, with posters at the entrance: an anxious-looking old lady, a child with a bandaged head, blood seeping through the gauze; a slogan reading like a poem:

Wondering about its punctuation and typography, I open the app and punch in:

Hawksmoor →

Hawksmoor Spitalfields ● Carefully sourced & aged stakes, ££££

The City Point tower deserted except for two girls entering: cleaners? Florists? A Carrot Cars driver waiting for someone, presumably with ££££ to spend. A billboard announcing “Europe’s largest construction project,” with “10,000 people working at 45 sites.” A dozen of them, all dressed in orange, descend the scaffolding from the tower in single file, putting their hard hats on, reluctant to honor God on the day of rest. One of them stops to give directions to a woman, who never stops talking on her mobile. On the billboard, under “Archaeology”, some info: “The most important archaeological site on the Crossrail route, excavations have revealed 2,000 years of London’s past. From a Roman road and timber buildings, to the ‘lost’ Walbrook River and the infamous Bedlam burial ground, the site is providing new insight into ancient Londoners’ lifestyles.”

“Moving London Forward”, reads a slogan on the fence. “Moving Safety Forward”, reads another, on the scaffolding. Nick Dyer looked for innocent victims—children, tramps, prying colleagues—to consecrate his churches. These builders might sacrifice somebody too and bury them in the foundation pit, where “ancient Londoners” and Bedlam inmates once lay. I double back and come to Liverpool Street train station, busy with people waiting for late-running Sunday “services” (“trains” having long gone out of use), one of them bound for Ipswich. Sebald would take it were he alive and on his way home, to the village of Poringland, next to Framingham Earl.

Returning to Moorfields on a weekday, I see a Big Issue seller offering copies aptly headlined “God Only Knows.” A few hundred yards down Moorgate stands a man with a bunch of leaflets titled—no less aptly—“Is Satan Real?” City traders walk around, demonized by the media yet not scary. Some of the lunchtime crowd may even be software developers, about to create an app with more dynamic features than ever.

Near Resolution Plaza, a board advertising a café confusingly called “Loves, the Little Kingdom of Great.” Not far from it, another, “Vital Ingredient,” its slogan somewhat unfinished: “Eat Your Way” (through what?). An arch with a sign reading “Light Centre: London’s Leading Wellbeing Centre,” advertising yoga and pilates classes, as well as an establishment called “CRUSSH : Fit Food.” I can hear Master Dyer, the great adept of Shaddowe and Darknesse, laughing at the sight of office workers going inside. Tapping the Google Maps icon one more time, I type in:

Sacrifice →

Self Sacrifice Tattoo ● Body Piercing Shop, permanently closed

As I poke around Moorfields, passersby occasionally stop to look at me; some start taking photos of the construction site, where all the builders have miraculously disappeared. A man pulls his dog’s lead short, stops before drawing level with me, thinking I’m about to take a picture of the hoarding. Looking at the screen of my phone, with its blue pictogram, I remember Sinclair’s arrow-shaped poem, which ends with a sharp point:

Forty years on, the alternative is to trust Google, if it can find you. The society of the spectacle is still mediated—multimediated—by images, as in the days of the Situationist International. You—and everyone around you—are still the spectator and the spectacle. A customer and a commodity rolled in one, you observe to be observed. At the end of his journey (and of Ackroyd’s story) Hawksmoor reaches Little St Hugh, as Dyer did three and a half centuries before him, enters the church and sits in a pew:

Back in the café with the two friends in search of the third, I listened to their conversation about Africa, where he was traveling, and the app that allowed them to locate him. I was torn between two feelings: if they can watch his movements in the Sahara then modern technology is no longer the privilege of the West; on the other hand, that means the conspiracy between internet giants and their customers is growing truly global. “The question of the use of technological means…is a political question.”19 Perhaps I should write about this conspiracy, I thought, but then again, wouldn’t that be tantamount to my complicity in it? And what’s there to write if all I can do is observe and be observed? Mulling over these questions, I stared across the table at the arrow chasing the circle.

1 Iain Sinclair, Lud Heat: A Book of the Dead Hamlets (Gloucester- shire: Skylight Press, 2012), 16.

2 Peter Ackroyd, Hawksmoor (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1985), 166.

3 Sinclair, Lud Heat, 19.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid., 102.

6 Email correspondence,

7th October 2014.

7 Guy Debord, Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, last modified 6th August 2007, accessed 9th June 2015, Web.

8 Guy Debord, “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography,” ed. and trans. Ken Knabb, Situationist International Anthology (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006), 8.

9 Constant, “Another City for Another Life,” ed. and trans. Ken Knabb, Situationist International Anthology (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006), 71.

10 James Ball, “Google Maps: Thanks for the app, here’s my personal data,” Guardian, 13th December, 2012, Web.

11 Guy Debord, “Introduc- tion to A Critique of Urban Geography,” Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, 11.

12 TV Kultura, “Ekologiya literatury (Ecology of Literature),” 14th August 2009, accessed 9th June 2015, Web.

13 Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven F. Rendall (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 201.

14 Iain Sinclair, “Diary,” London Review of Books, Vol. 36, No 21, 6th No- vember 2014, 46-47.

15 Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, trans. Ken Knabb, accessed 9th June 2015, Web.

16 TV Kultura,“Ekologiya literatury (Ecology of Literature).”

17 Sinclair, Lud Heat, 102.

18 Ackroyd, Hawksmoor, 216-217.

19 Guy Debord, “Perspectives for Conscious Changes in Everyday Life,” Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, 95.

Anna Aslanyan is a journalist, literary translator, and public service interpreter. She grew up in Moscow and lives in London. Her writing has appeared in a number of publications, including 3:AM Magazine, The Independent, London Review of Books, and The Times Literary Supplement.