Missed Connections: Aby Warburg & A Theory of Curtains

For years, whenever I have published an essay, usually on the subjects of art, literature or the connections between both, I’ve been asked for a brief biography. And for years this bio mentioned that I was at work on a book on cloth as both subject and medium in art.

It’s true that I have—in fits and starts—been working on such a book, but it is only recently that I thought to ask: Where did the idea for this book that connects modern and contemporary art to late medieval and renaissance art come from? I was able to answer this question, to myself, immediately: The book began with an obsession with two moments in history—one a missed connection and the other an absence. Maybe the idea for the book was bound up in a desire to remedy both a rejection and a failure. Better, of course, to deal with someone else’s rejection, someone else’s failure, rather than dwelling on my own, which seems as good a reason to write a book as any.

The missed connection is this: In the mid-1920s, the German philosopher-critic Walter Benjamin sought to connect with the scholars who had gathered around the art historian Aby Warburg in Hamburg. Benjamin particularly admired a 1923 publication by the Warburg Institute coauthored by Erwin Panofsky and Fritz Saxl on Albrecht Dürer’s “Melencolia I” engraving. With Benjamin’s urging, the editor of a journal who had published Benjamin’s own essay on melancholy, shared an excerpted portion of his book on The Origin of German Tragic Drama with both Panofsky and Saxl. The cool and mostly indifferent response from Panofsky (in a now lost letter) left Benjamin apologetic for bothering the journal editor, at a time when Benjamin was also getting the run-around by another editor who had once promised to publish his work but kept putting him off.

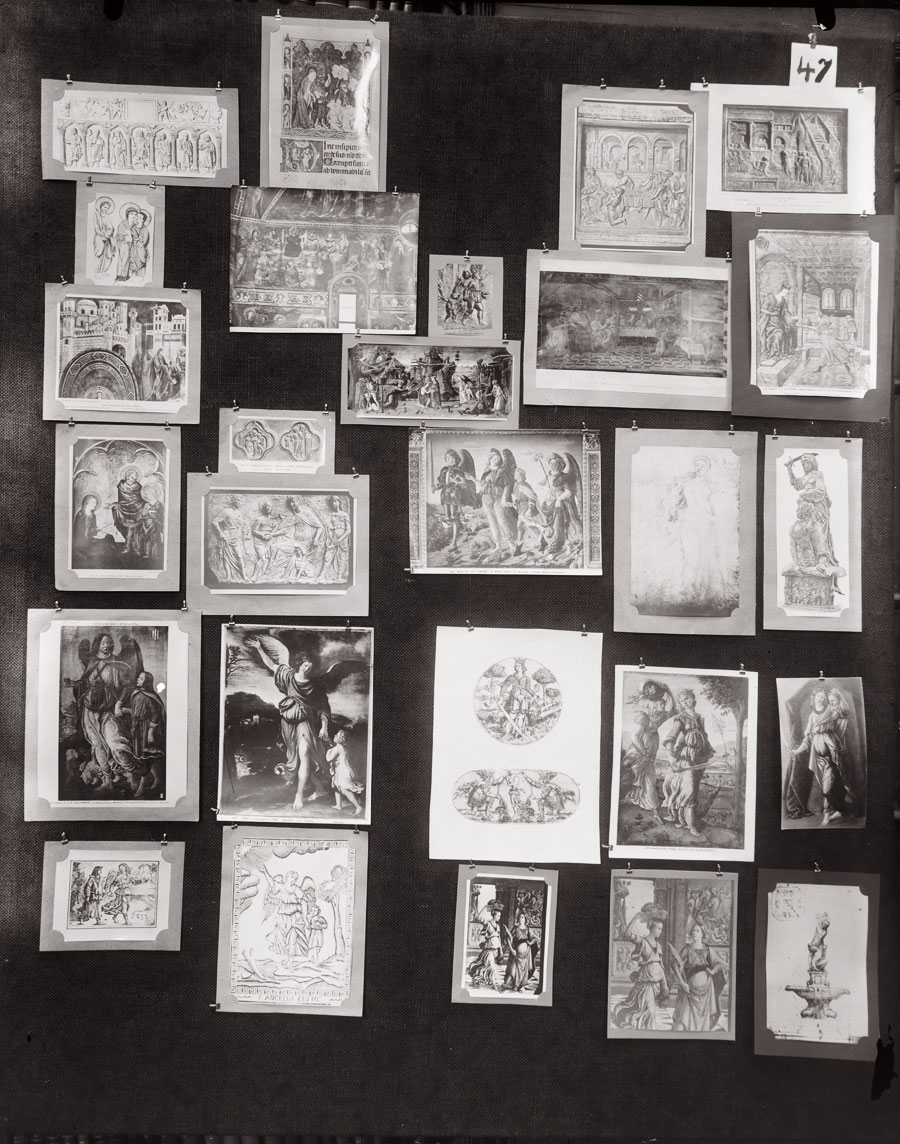

What is remarkable to me is this—Walter Benjamin was somehow at once developing his powers as one of the greatest critics of his generation and, yet, also entering his flop era. Benjamin could have been the bridge between the Frankfurt School (with which he is now associated) and the Hamburg group. But it never happened. Still, I think of Benjamin’s unfinished masterwork The Arcades Project, a collection of fragmented notes on the birth of the modern in poetry, art and design, and the proto-mall, as a project kindred and forever-paired (for me at least) with Aby Warburg’s similarly fragmentary, sprawling and never-completed Mnemosyne Atlas; a work which traced the persistence and repetition of images from antiquity into the modern, from ancient art to modern advertising, by posting an array of black-and-white photo reproductions on black cloth-covered panels.

It’s not, you see, that if they had connected, either of them would have been any more likely to have finished their projects. It’s that I think they would have deeply understood the critical frameworks that motivated their obsessive projects.

I always think of Benjamin’s experience of rejection by the Hamburg group as paired with another moment of failure. Intellectually exiled and adrift on the island of Ibiza in 1933, Benjamin made experiments out of the practice of occasionally getting stoned and recording his experiences with hashish. On one occasion, while experimenting with opium, he sat in his chair and stared out the window, distracted. He was taken with the simple image before him, of a curtain gently dancing or drifting in the window, its translucency and lacework making itself active and present as a thing between the world inside and the world beyond.

In a letter he promises to provide a theory of this, a “rideaulogie” or theory of curtains. Of course, he never actually writes this. And maybe he doesn’t need to. I find the stoned-out aspect of this whole scenario a little embarrassing for an intellectual giant, adrift without any financial or institutional support, except the help of some friends. But what else was he to do, wandering, exiled with fascism spreading and Nazis arriving even to Ibiza?

Benjamin would return to Paris and to the Bibliothèque Nationale to work on the Arcades Project, which survives because the writer Georges Bataille worked as a librarian there and hid it in the archives as Benjamin fled the Nazis to eventual suicide near the border with Spain where he had hoped to escape.

Instead of a failure, I see a condensed flash of insight. Isn’t all that succeeds as art like this a curtain drifting in the wind? A thing to be considered that exists between our interiority and the world outside? An object that bridges the gap, that we can witness together, something dancing upon a membrane between what is mine (or yours) alone and what can be shared together? This is all I want to chase after: a theory of curtains.

John Vincler is a writer, artist and critic living in Brooklyn. His art reviews regularly appear in The New York Times. He is working on a book-length project about cloth as a subject and medium in art.