I like clothes. I enjoy looking at what people wear. If I could start my career again, if I could learn a trade, I’d train to be a tailor. But it’s too late for that. I’m a forty-something writer and I have little cash to spend on shoes or shirts. My best clothes are hand-me-downs from my older brother, Mark, who has dressed beautifully since he was a teenager.

Mark got me into clothes originally. Not just clothes, but the specific pleasure of shopping for them. He taught me to savor the search for what you didn’t know you wanted; to read fabric, understand how clothes made you carry yourself, imagine the potential an item might have for a new outfit in combination with something you already owned. Above all, Mark showed me that great personal style didn’t necessarily derive from what was expensive or in fashion, which was solid advice since neither of us had much money.

Mark was pairing the new with the old as far back as the early 1980s. Nineteen-forties de-mob suits, ‘60s paisley shirts, art deco-era sunglasses, Italian shirts. The latest New Romantic or soul boy styles. Then, as now, he looked knockout. This was before that mendacious word “vintage” and an inflationary price tag was slapped onto any old tat. Mark knew where the best secondhand places were found. He understood how to assemble a unique and elegant look on a tiny budget.

We grew up in a large village outside Oxford in the southeast of England. The city was a 20 minute bus ride away. A short little Oxford thoroughfare, Little Clarendon Street, used to be home to a handful of good independent clothes shops, the names of which now escape me. You could find old gentleman’s outfitters in the city—the shoemaker Ducker & Son, for instance, founded in 1898 and closed down in 2016—along with a branch of London’s Selfridges department store. There was a peculiar secondhand place—still going today, to my surprise—called Unicorn; a tiny, musty shop, that looked like it had been carved out of mounds of ancient dresses and suits. Oxford had a couple of army surplus stores where you could pick up West German army jackets, combat boots and khaki rucksacks, which were then popular with students and kids into alternative music. Everyone customized their army bags: I painted a large Primal Scream Screamadelica sunburst on mine. Cult Clothing, long defunct, was next to the bus station, and was the place to get skatewear and baggy fit jeans, which came in a wide range of dyed colors. Everyone at my high school seemed to have a pair: I think I had them in dark green, or it may have been deep purple, I can’t recall now. Sportswear—brand sweatshirts and sneakers worn by casuals and ravers—was easy to come by in town. Record stores and music venues were the places to get your oversized band t-shirts. XL-size Stone Roses and Happy Mondays were a common sight. I had a white-and-yellow Ride one, which I loved. The village I grew up in was not the safest place to be if your clothes stood out—it could be a bit rough at times—so I kept a couple of plausible disguises in my wardrobe. Sneakers, sweatshirts, an acceptable cut of jeans, items that wouldn’t attract the wrong kind of attention.

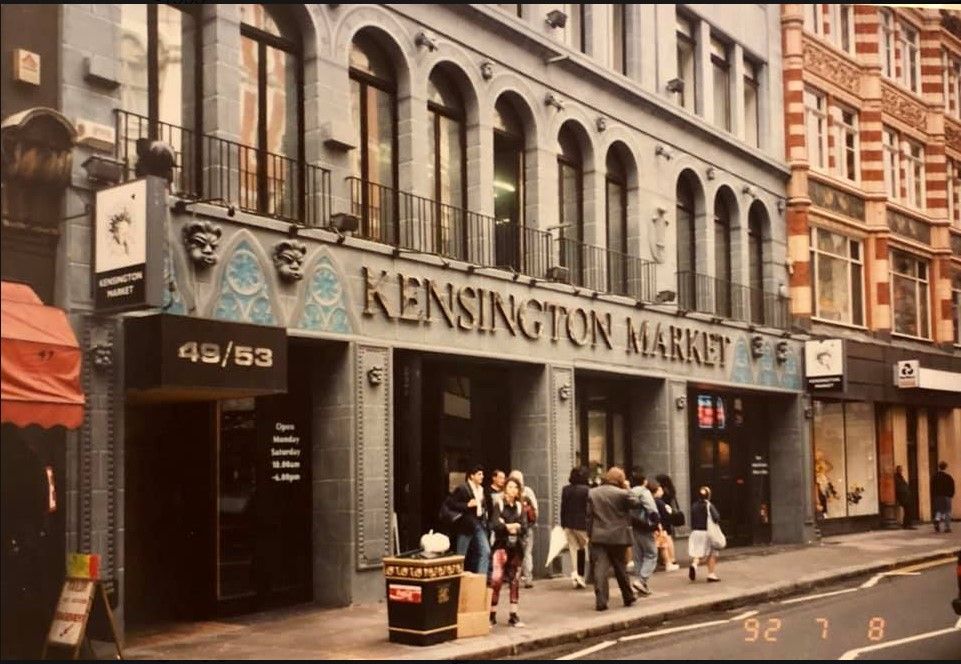

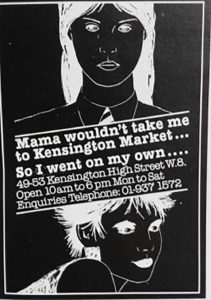

It was around the age of 16 that my taste in clothes began to drift from average teenage indie kid into more idiosyncratic waters, and I longed for more than what Oxford had to offer. I was learning from Mark about art and music from the 1960s and ‘70s, expanding my tastes. My brother used to make shopping expeditions to London in the early 1980s, and when our parents allowed me to start doing the same in 1992 or ‘93, he provided me with a list of stores to check out. Chelsea’s King’s Road had been his stomping ground, the zenith of post-punk streetwear in his day. By the time I started going up to London, Chelsea’s best places were mostly gone. Flip, which had started in the late 1970s and sold American gear from the 1950s and ‘60s—real American Graffiti stuff—was one holdout, as was Kensington Market, which was going into decline but still had clothes impossible to find back home. The market, which closed in 2000, was a warren of booths in a large three or four-story building, where goths, punks, ravers, oddballs from the industrial scene and indie kids could acquire their tribal looks. Mark had told me about a place there which sold 1950s and ‘60s retro styles, and where the changing rooms were in the shape of coffins. He may have been describing a spot in Hyper Hyper, another market-type establishment next door to Kensington Market which was a showcase for young designers. Most likely he was talking about Johnson’s which had a sister store on the King’s Road. I never found the coffin booths, but it was at Johnson’s in Kensington Market that I bought a sandy-colored moleskin jacket with silver popper buttons, wide pointed lapels, and burgundy silk lining, made under their 1950s-influenced label La Rocka. I gave it to a friend some 20 years ago, and to this day regret doing so.

It was around the age of 16 that my taste in clothes began to drift from average teenage indie kid into more idiosyncratic waters, and I longed for more than what Oxford had to offer. I was learning from Mark about art and music from the 1960s and ‘70s, expanding my tastes. My brother used to make shopping expeditions to London in the early 1980s, and when our parents allowed me to start doing the same in 1992 or ‘93, he provided me with a list of stores to check out. Chelsea’s King’s Road had been his stomping ground, the zenith of post-punk streetwear in his day. By the time I started going up to London, Chelsea’s best places were mostly gone. Flip, which had started in the late 1970s and sold American gear from the 1950s and ‘60s—real American Graffiti stuff—was one holdout, as was Kensington Market, which was going into decline but still had clothes impossible to find back home. The market, which closed in 2000, was a warren of booths in a large three or four-story building, where goths, punks, ravers, oddballs from the industrial scene and indie kids could acquire their tribal looks. Mark had told me about a place there which sold 1950s and ‘60s retro styles, and where the changing rooms were in the shape of coffins. He may have been describing a spot in Hyper Hyper, another market-type establishment next door to Kensington Market which was a showcase for young designers. Most likely he was talking about Johnson’s which had a sister store on the King’s Road. I never found the coffin booths, but it was at Johnson’s in Kensington Market that I bought a sandy-colored moleskin jacket with silver popper buttons, wide pointed lapels, and burgundy silk lining, made under their 1950s-influenced label La Rocka. I gave it to a friend some 20 years ago, and to this day regret doing so.

Designer clothing has never been my thing. As a teenager I was interested in what was going on at street level. Although a lot of the music I was into then was forward looking—jungle, techno, the left of leftfield alternative music—the clothes I desired were all old. I loved how people dressed in photographs from Andy Warhol’s Factory of the 1960s. I adored punk and mod-revival fashions from the late 1970s. Jean Seberg in a striped t-shirt in Breathless; Scott Walker in turtleneck sweater and shades; Bowie in high-waisted flared trousers on the back sleeve of Hunky Dory. I wanted to look like all of them, but I found it hard to find what I needed in order to do so and did not have the time or resources to dredge London for what I was after. As a result, my wardrobe included a lot of approximations and compromises. My manifesto was Jon Savage’s liner note for the 1991 Saint Etienne album Foxbase Alpha. He crystallized the way I wished to put my world together, describing an afternoon shopping in London, searching out the latest acid house tracks dressed in 1960s-style clothes. Savage provided me with a blueprint to reconcile my taste for the past with what I instinctively knew was a future-facing moment in British youth culture that I mustn’t miss.

I poured over magazines such as The Face and i-D, because I wanted to know what was going on beyond my small town. On trips to London, I’d make an effort to scope out what was new, because at some conceptual level I understood that this was what you should do if you wanted to enjoy your own zeitgeist, but I didn’t feel attracted to many of the clothes on offer. For instance, I remember visiting Duffer of St. George’s now long-gone store in Covent Garden in the early 1990s, long before that label jumped the shark. All the magazines were talking about Duffer, bands I admired were wearing it, but it was way out of my price range and their preppy-meets-streetwear look never did much for me. I preferred the vintage shops around the corner. There was Blackout II, which was then run by an older woman who looked the spitting image of actress Frances de la Tour, whom I knew from re-runs of the sitcom Rising Damp. I believe it was here that I found a superb black leather jacket with a huge zipper and bat-wing shaped yoke back. I lost it playing a gig with band in Brighton one night in the mid-2000s, and I long for it now like I miss the La Rocka moleskin. And then there was the wonderful Cenci. Cenci was run by an Italian husband and wife; their store was located in Covent Garden just yards from the Neal’s Yard branch of the Rough Trade record store—a heavenly pairing for a shopping trip. I remember rummaging through huge stacks of Italian knitwear, the kind of knits that would be unaffordable today. I bought at least two vintage ski-sweaters from Cenci, my favorite of which—cream, with two wide horizontal bands of red and blue—I spilled coffee on. It was never the same again. Cenci closed and left central London for the suburbs in the early 2000s.

My interest in retro looks dropped away in the early 2000s after moving to London. I had started working as an art magazine editor and begun to learn new vocabularies of clothing from artists and writers who were a little older, a little more sophisticated, than I was. This was exciting, even if I did feel like a hick again. But I struggled for a while to find clothes I could both like and afford, and for a while I felt out-of-sync with what London’s stores had to offer. Gradually, almost imperceptibly, independent clothes stores were on the wane, increasingly replaced by corporate chains and luxury brands beyond my pocket.

In the late aughts I discovered a shop just off Regents Street called Other. They had started out with the B-Store shoe brand, and now ran their own in-house menswear label and carried clothes by young designers. I loved what they did; understated, now, elegant without being minimalist-bland. Most importantly I appreciated how the sales staff made me feel. It evoked the way Mark talked to me about clothes. The interactions were conversational. They took their time to find something out about you, looked at what you had worn that day and made suggestions, yet never pressed you to buy anything if you weren’t feeling it. Of course, they were great practitioners of the dark art of flattery. I remember one sales guy there—slightly built, always wearing eyeliner—whom I suspected could convince me to wear a half-eaten kebab and a bag of dead leaves if he wanted. But being charmed was part of the fun. You didn’t have to believe in it, just be willing to understand the role it played in the theater of clothing stores.

From Other I bought a beautiful pair of black, wide-legged, lightweight cotton trousers—a little Japanese in style, a little off-duty Bowie—which I still wear every summer. When winter comes I look forward to pulling out a big overcoat I also bought from them. It’s made from luxuriant, salt-and-pepper color wool, almost the texture of mohair, and makes me feel as if I am Michael Caine starring in a 1960s Cold War thriller. I’ve received more compliments from strangers about that coat than almost any other item I’ve owned. Other closed down six or seven years ago and I miss it.

Or rather, I miss conversation about clothes. My experience of clothes shopping since I moved to New York has been a solitary one. Mark lives thousands of miles away back in the UK. There are fewer places to go in New York now. And men, straight men at least, don’t talk enough about what they wear or why. A wedding or special occasion might drag out a brief compliment—“looking sharp,” “nice duds”—but rarely will you hear men stray further into a more detailed appreciation of cut, drape, color, and fabric. In my experience, those men who do seem interested in clothes prefer to flash their knowledge of arcane fashion lore, or their expertise on the current market price for vintage items. This, to me, avoids talking about what clothes do. In the press, conversation about menswear too often comes under the rubric of how to acquire the ultimate “gentleman’s wardrobe,” and other appeals to a bullshit canon of masculine sartorial classicism. It leaves me cold. I don’t want to look like everyone else. Serious thought around what men put on their bodies is depressingly attenuated and void of sensuality—not in the erotic definition of the word, but in terms of how clothes make you feel, how fabric draped on and wrapped around skin acts, what it does to you, where the pleasures are.

Clothing is marketed to men like cars or tools. A pornographic inventory of durable parts: goodyear welted soles, bar-tacked triple-stitched belt tabs, Japan-milled rinsed 14-oz indigo yarn-dyed denim with red-ticker selvedge, insulated to temperatures of minus-10 degrees fahrenheit. Macho appeals are made to—and lord how I have come to loathe this word—heritage. “Founded in 1921.” “The shoes are built on 75-year old lasts.” “These rugged jeans were originally fabricated for men hunting crocodiles in the New York City sewer system.” “The shirts are constructed using linen first sourced by roadside toga-makers on the Appian Way during the rule of Emperor Diocletian in 300 BC.” I want shoes, not a museum.

I seldom have conversations about clothes with other writers. Occasionally with artists, rarely with musicians, and never with filmmakers, who in my experience dress far worse than writers do. You’d think, given how much observation is involved in the craft of writing, that authors would be full of opinions about what people put on their bodies. There are plenty of writers who know about fashion but knowing about next season’s Eckhaus Latta or Balenciaga collections says nothing about what people mean by what they wear, whatever that may be. My girlfriend Sarah is the only other writer with whom I talk to about clothes, and in this I am lucky since she has more style than I do. The best conversation about menswear that I’ve had this year has been with my friend Michael who is training to be a psychiatrist. Take from that what you will.

At this stage in the immiseration of city life, writers are practically professional mourners at the passing of bookshops and record stores, of the beloved bars, cafes, cinemas. Strangely, their keening never reaches as far as independent clothing stores, which you’d think they’d need after all that rending of garments. These are as much a part of a city’s culture as repositories of words and music are. When, in the midst of lockdown, it was predicted that we would never again leave the house and only buy trackpants and pajamas online—when the grim term “hard clothes” was coined to describe jeans, suits and shirts—I felt profoundly depressed. Shopping online for books is a flat experience but not half as much as looking for clothes is, which comes with the exhausting prospect of having to send the item back if it doesn’t fit. MatchesFashion or Grailed won’t flatter you. They won’t even play snooty sales assistant and neg you with disdain at your choice of outfit. Online, you can enjoy a brief window of fantasy that the jacket you’ve just bought will, when it arrives, fit you perfectly and make you infinitely more attractive. At a brick-and-mortar shop, where you can try things on, feel them, understand what they do on your body, your eyes will be given the hard truth right away. It doesn’t suit you. You look like a gift-wrapped cabbage. What were you thinking. But, as people—writers!—love to say about bookshops, the best experience involves chance encounter with something you didn’t know you were looking for. A conversation you didn’t know you were going to have. I want surprise, I want sales patter, I want to see how other people present themselves to the world.

I’m digressing, I know, but that’s the point of conversation when you’re out to browse shoes on a Saturday afternoon.

Header Image: Johnson’s interior, Kensington Market, King’s Road [Source].

Dan Fox is a writer, editor, filmmaker and musician based in New York. He is the author of two books—Pretentiousness: Why It Matters (Fitzcarraldo Editions and Coffee House Press, 2016) and Limbo (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2018)—and has contributed to a wide range of exhibition catalogues and institutional publications. His BBC-commissioned film Other, Like Me: The Oral History of COUM Transmissions and Throbbing Gristle (co-directed with Marcus Werner Hed) was shortlisted for a 2022 Grierson Award.