Hanoi, Vietnam

June 2023

One night, in early 2014, I was trying to decide what movie to watch. I needed something new. Well, that is, I wanted to watch an older film but one free from personal associations. My life was in the middle of a difficult transition, and I desperately wanted to watch something that couldn’t be tied to anything or anyone in my past.

I scrolled through movie files on my hard drive. Eventually, my mouse hovered over a file called Margie. I looked it up. It was from 1946 and directed by Henry King. I admittedly didn’t know much about King, outside of his name that I’d occasionally come across through my job as a video archivist. A description of the film said it was about a young high school girl, her crush, and her experience on the high school debate team. I fired up the VLC player on my laptop and put it on.

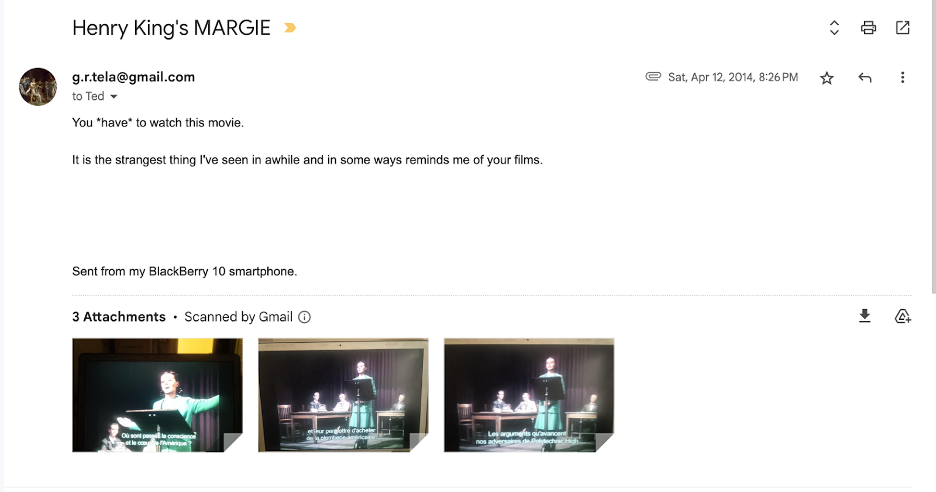

I was immediately struck by the outdoor locations, the bright blue sky, and how it contrasted with many of the interior shots, which were shockingly dark. I also found Margie’s structure—the loose and ambling flow, its concern of characters over plot, its equal love of the goofy and the gallant—to be quite modern. In fact, it reminded me of my good friend Ted Fendt’s films. I wrote to him as soon as the movie ended.

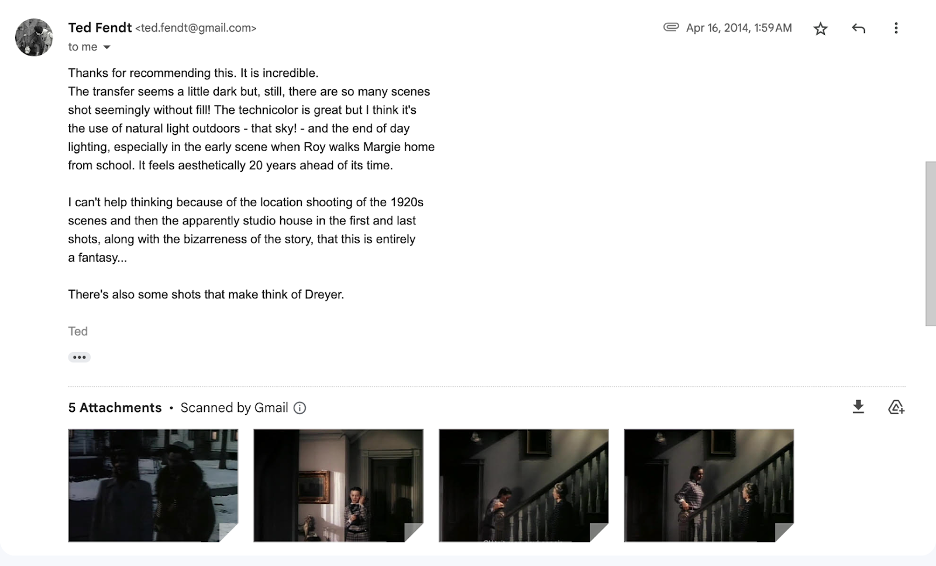

A few days later a reply came:

The .avi file we watched was downloaded from a private torrent community and originated from a broadcast on French television. I later made a new file, one without French subtitles, from a burned DVD acquired from a private video collection. That DVD featured a version of the film that aired on the Turner Classic Movies channel (TCM) in the United States. As of this writing, there is no commercial DVD of Margie available for purchase and you can’t access it legally via any streaming platform.

Ted and I started watching more King films, especially those, like Margie, in the loose genre of Americana. Like many directors from Hollywood’s Golden Era, King worked prolifically, directing some 116 films between 1915 and 1962. We sourced his films from the aforementioned private torrent community and I continued to borrow DVDs—both commercial and burned off of TV broadcasts—from the private collection that I had accessed for Margie.

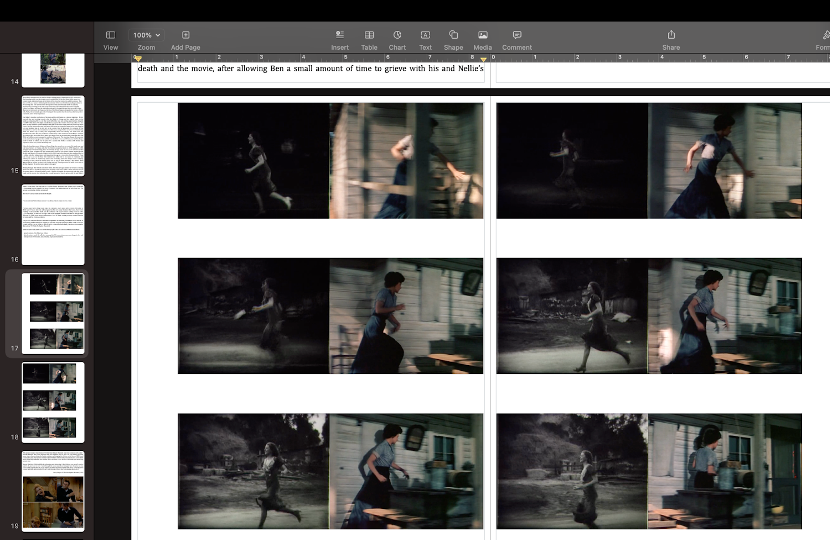

The emails continued between myself and Ted, full of discovery that felt as though we were looking forward instead of back. Some were serious examinations of form, of King’s use of camera movement and his often-expressionistic lighting. At other points our notes took the form of stray thoughts about a character, a bit of dialogue, or a specific shot or idea. The films may have been made in the past and set in the even farther back past, but our discussions were firmly in the present and beyond.

Hanoi, Vietnam

February 2025

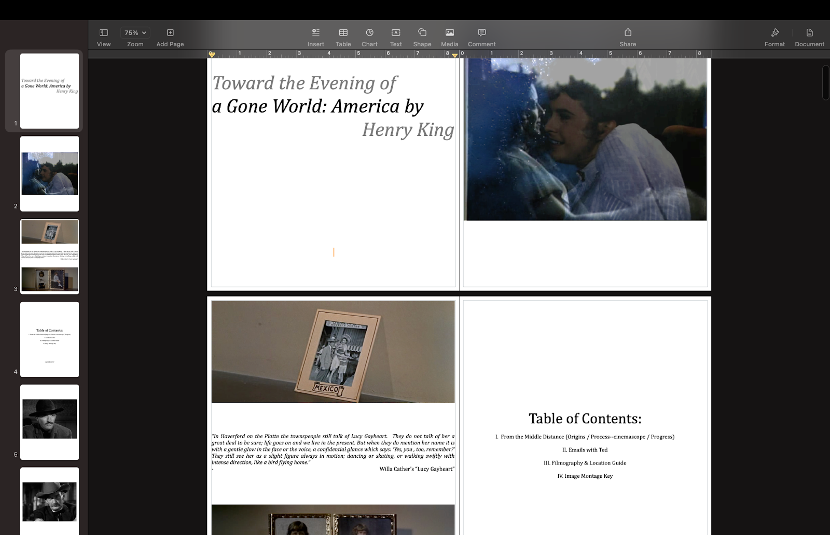

After watching Margie, I started to collect and create materials—words and images—in hopes of putting together a book on Henry King. The previous text could be considered an excerpt from what I hoped would be the introduction.

It’s a project I genuinely hoped to make good on in 2023 while in Hanoi for a few months, away from the hustle and bustle of my daily life in New York City. Over those months I again sent friends files of Kings’ films and we exchanged excited emails and voice memos about them, reinvigorating many of the ideas that Ted and I had discussed almost 10 years prior. It was invigorating to realize how alive the films still were. I dove back into the seemingly endless pieces and parts I had constructed over the years…

I made some progress while in Hanoi, but those hot months passed and eventually I was back in New York City. Life came at me full force and I was no longer able to manifest the time and focus needed to complete the project.

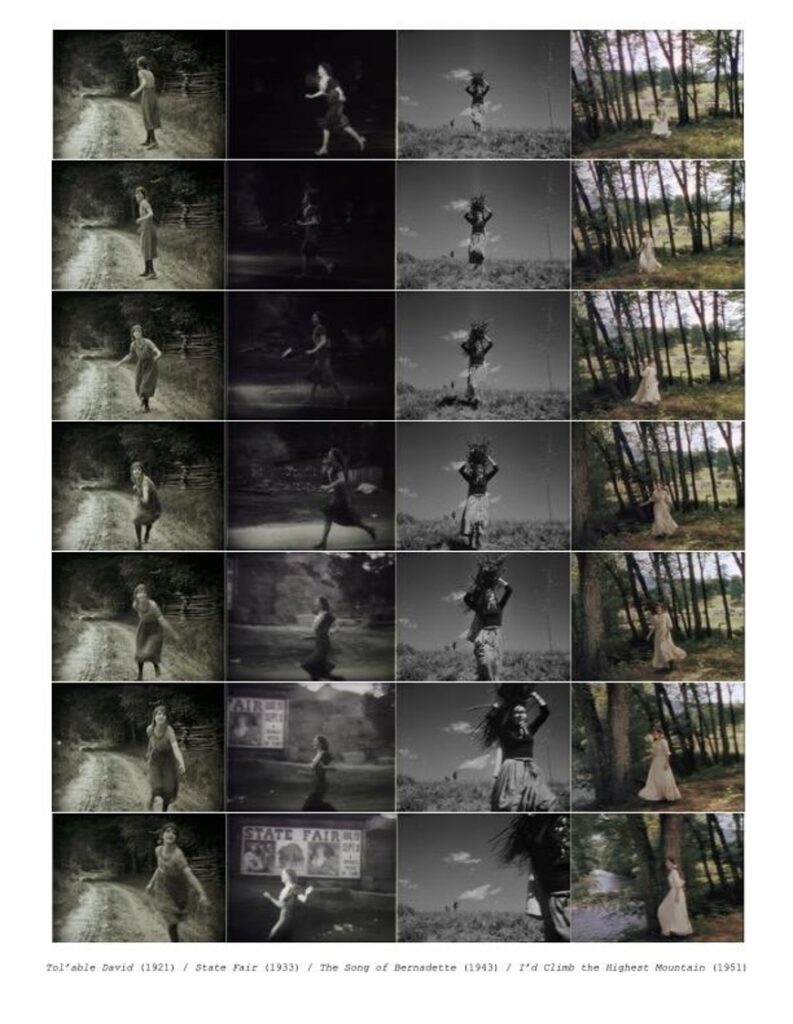

It’s disappointing but perfectly fitting that life, with all its plotless twists and turns, would get in the way. His are films that examine life; how his characters live, who they do that living with, and the life they move through. He is especially attuned to place, using wide-angle lenses to open the shot and capture the details of his characters’ surroundings. King was a pilot and whenever possible he would hop in his plane and fly across the country, sometimes the world, searching for the perfect location to shoot his story.

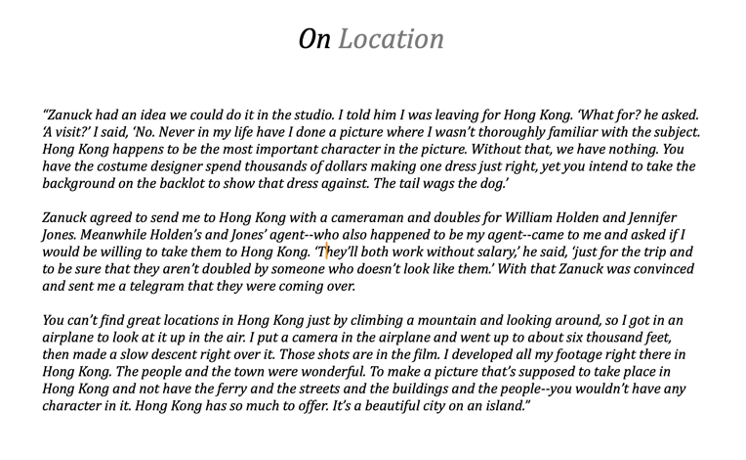

When on location, he focused on community—both on screen and off—and on how groups of people affect each other and the possibilities therein. I often think of a story, one I intended to include in my book, that he told in his oral history about his film Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing (1955), which is set in Hong Kong:

This account was taken as part of a Director’s Guild of America book series that is now out of print and only available via used book sites for well over $100 USD. Similarly, Walter Coppedge’s Henry King’s America, written in 1986, is not only a great King resource but is easily one of the best film books I’ve ever read. It’s also out of print. I came across it on the shelf at work and my boss thoughtfully, and miraculously, procured me a copy when he learned I was interested in King’s films.

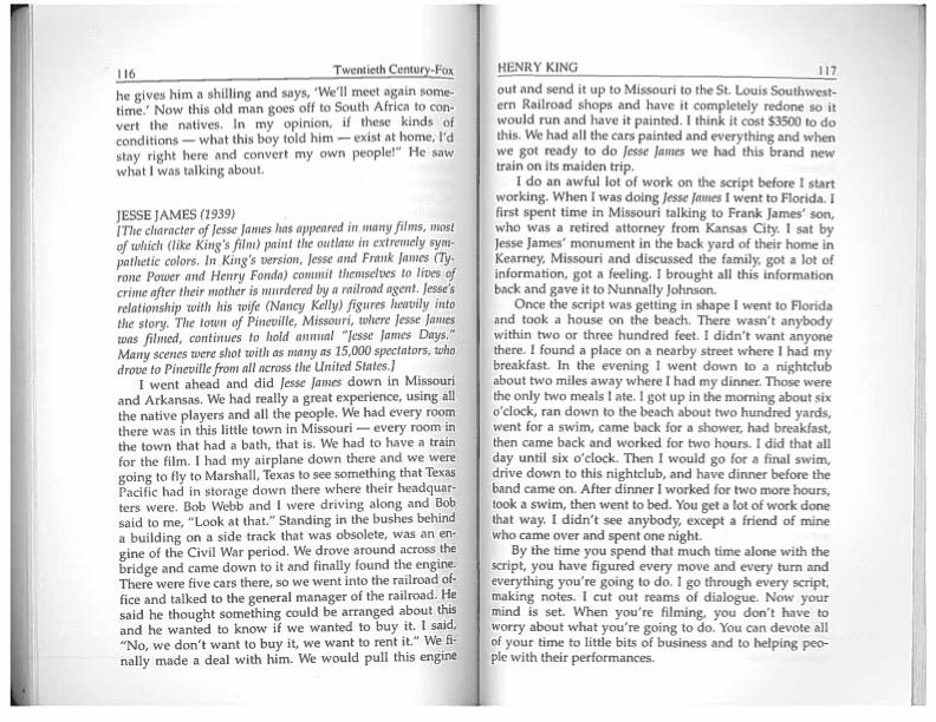

When speaking about the making of his 1939 masterpiece Jesse James for the DGA oral history series, King spoke of a process of working, the circumstances needed to create, that I think about often.

How we live has changed rapidly and quite dramatically since I watched Margie back in 2014. I am currently in Hanoi, as I write this, and it’s a change I especially feel while here 12 hours ahead of New York. The days have a new rhythm. I wake up around 6am and eventually turn on my phone. The messages pour in and I make breakfast and attend to them. Starting around 10am my phone goes cold. New York, despite the saying, is mostly sleeping. I finish watching the illegal streams of the morning’s basketball games with my coffee and I move through the rest of the day quietly and in my own head, without endless incoming distractions. Possibilities, new ideas, slowly but surely begin to filter back in.

Rereading the King piece that I wrote here two years ago and looking through the “HENRY_KING” folder on my computer—at over ten years of ideas and work, ten years of watching and rewatching his films—it’s hard to not feel pulled to finish my project. But I also sense that the book I wanted to make is not for this moment. And that’s OK. The files remain and, in this digital iteration, they’re still usable. I recently migrated them to a new hard drive and I’ll do it again in a few years.

In 2020, the Criterion Collection released King’s The Gunfighter (1950) on Blu-Ray/DVD and they asked me to speak on camera about the film and the filmmaker for the disc’s special features. Apart from that, it’s a curious feeling to have this wealth of knowledge with so rarely a use for it outside of my own personal enjoyment and edification. On one hand, this saddens me deeply: King was instrumental to the creation of the art form and his films are bonkers inspiring. There is so much to learn from them! On the other hand, I feel hopeful that these films exist so vibrantly between small, thoughtful groups of people, making their way from hard drive to hard drive, voice memo to voice memo, email to email. These are the exchanges that will keep King, and films like Margie, alive.

Gina Telaroli is a filmmaker, cinema worker, and dedicated fan of the Cleveland Cavaliers basketball team. She works for The Film Foundation and is on the programming team of The New York Film Festival. Her latest feature film, IN SEARCH OF GLADYS GLOVER, premiered last year at The Roxy Cinema and Anthology Film Archives in New York City.