High Risk Books & Rex Ray: The Beginnings of a History

I. Kismet; Cruising Los Angeles

My discovery of High Risk Books was purely accidental: while living in New York a friend insisted I attend a talk at NYU for the launch of the English translation of Paul B. Preciado’s Testo Junkie, hosted and introduced by Avital Ronell. At the time, both figures were completely unknown to me. In the course of this talk, Preciado mentioned Guillaume Dustan’s In My Room, and queued up a slide with one of the most dazzling book covers I’d ever seen: a graphic rendering of the Eiffel Tower, the top half of which was set against a colorful collage of butt plugs. It was love at first sight. I immediately acquired this book, paying some $70 for the pleasure.

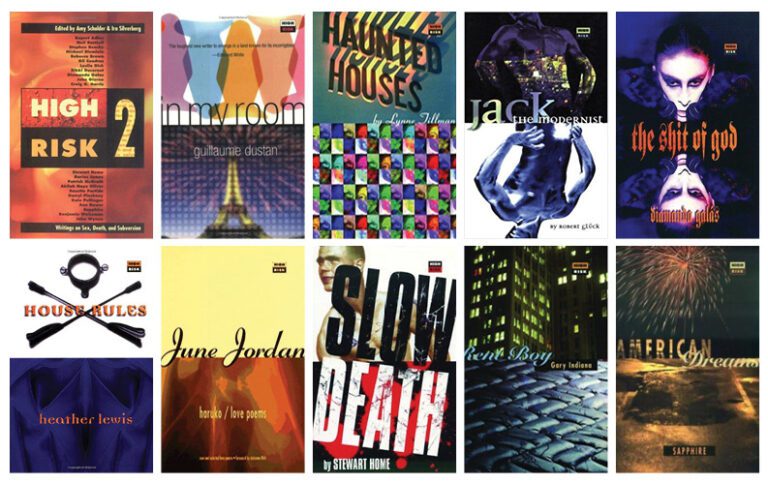

A year later, I left New York for Los Angeles, dragging an obscene number of books across the country with me. I loved In My Room, but I hadn’t spared much thought for the little logo adorning both cover and spine reading “HIGH RISK.” It can be rather difficult to orient oneself in Los Angeles, so I did what any mildly obnoxious, flaneuristic queer with intellectual pretentions in their twenties would do: slam down an endless amount of Chris Kraus, Reyner Banham, and other Los Angeles luminaries, while hitting up every bookstore in the city. It was at the now-defunct Circus of Books in West Hollywood where, in the course of hunting for other things, I saw a familiar logo on a book spine—this time for Robert Gluck’s Jack the Modernist. Still not quite putting two and two together, I made a fun little habit of keeping my eye out for these books while making my weekly circuit of used bookstores. Enough trips to Iliad Bookshop, Counterpoint, Book Alley, Circus of Books, and others led me to works by Stewart Home, Sapphire, Gary Indiana, Ann Rower, and even Diamanda Galas (I suspect an ex of mine is still cross that I found Shit of God before them, and for a mere $2). These striking books became a fun subject of conversation at endless openings and parties; sporadic curiosity about their history brought people like Kevin Killian back into my life; they even proved to be a point of bonding with certain friends of mine. Bit by bit, I was able to piece together a very patchy picture of High Risk Books.

Years later, a course I stumbled into at UCLA on the history of the book cover finally gave me the time and resources to properly begin investigating this hobby-cum-obsession of mine. High Risk is inextricable from my own personal topography of Los Angeles, and in many ways, it quite simply is my Los Angeles—and a Los Angeles that, at times, feels as though it grows ever more distant as my life and its many attendant desires change. The history of High Risk Books is still an incomplete one, though it brings me great joy to share the fruits of my inquiry with any and all fellow travelers.

II. High Risk: A Pre-History

High Risk Books was a short-lived imprint of Serpent’s Tail, an English press founded in 1986 by Pete Ayrton with a reputation for publishing edgy writing, particularly writing in translation. Founded by Amy Scholder and Ira Silverberg, High Risk ran from 1994 to 1997, publishing some 40 books before financial difficulties forced Serpent’s Tail to close it down. Prior to the publication of such novels as Sapphire’s American Dreams and Gary Indiana’s Rent Boy, Scholder and Silverberg edited a collection of writing titled High Risk: An Anthology of Forbidden Writings published in 1991. Showcasing writers like Kathy Acker, Mary Gaitskill, Dennis Cooper, Essex Hemphill, Gary Indiana, and others, Scholder and Silverberg were responding to a crisis of self-censorship exacerbated by the AIDS crisis:

“High Risk is not an AIDS book, but of course, AIDS has impacted our lives, all representations, and how we read them. The premature deaths of some of this generations most wild and creative artists and writers change everything. How to have sex, how to take drugs, how to form community when anti-sex fascist have used AIDS to isolate us from one another—these are the challenges faced by the contributors to this anthology, as well as artists and writers, in the form and content of their work.” (Scholder and Silverberg xvii)

The assemblage of writers for the High Risk anthology was quite revolutionary at the time. Putting together writers like Gaitskill, Cooper and Indiana—or Dodie Bellamy and Bob Flanagan—seems perfectly normal today, however this was published ahead of their currently-established reputations, and done during an era in which writers like Randy Shilts, to say nothing of out-and-out monstrous bigots like Andrew Sullivan were trading in pernicious anti-sex respectability politics, admonishing and shaming gay men in particular for the crime of bodily sociability. The anthology also featured a logo designed by the artist and graphic designer Rex Ray, who would later incorporate it into his graphic design for all the imprint’s book covers.

Scholder had edited a precursor of sorts to the anthology in 1988 while working both as a clerk at San Francisco’s City Lights bookstore and as a junior editor at the City Lights Review. Spurred by the negative impact of the AIDS crisis on cultural life, Scholder sent the following statement to a diverse group of artists and writers:

“When government and mass media exploit the vulnerability of certain people with AIDS… an oppressive morality is reinforced and diversity is threatened. Today, a community is emerging to work toward change, and artists and writers have been responding with their work and with their lives,” (Scholder 1988, 7).

To her surprise, everyone she solicited responded favorably to participating and she was able to publish a forum on AIDS and cultural life featuring work from David Wojnarowicz, Edmund White, Lynne Tillman, Karen Finley, Sarah Schulman, and a number of other queer, feminist luminaries. This became the second issue of the City Lights Review and placed her on the radar of Ira Silverberg; their collaboration and success with the High Risk and later High Risk 2: Writings on Sex, Death, and Subversion (both published by Plume, itself an imprint belonging to the Penguin Group), brought them to the attention of Pete Ayrton, who then gave them their own autonomous imprint under the auspices of Serpent’s Tail.

III. Organization & Operation of High Risk

High Risk was structured in a unique way: while Scholder and Silverberg each brought authors in for publication, the bulk of editorial responsibilities fell to Scholder, while Silverberg dealt primarily with publicity. From the beginning, they wanted High Risk to have an enticing visual identity and instant recognizability. Given High Risk’s mission to foster challenging and transgressive work from largely unknown authors, a strong brand could act as a cohesive mark of identity across their catalogue and instill trust in readers that a High Risk book would be worth their while. Those already disposed to buy recognizable authors like William S. Burroughs or Gary Indiana would thus also take a chance on lesser knowns like Sapphire and their book American Dreams. Towards this end, Scholder brought Rex Ray on board to handle the design of High Risk’s brand identity and the covers for each book the imprint published.

Ray and Scholder already had a working relationship. Together they worked the Thursday night shift at City Lights bookstore for a number of years, and Scholder frequently commissioned Ray to design covers for the City Lights Review. Given their history and friendship, Scholder let Ray run wild with the High Risk covers.

Designing a book cover presents a challenge to any designer: despite admonitions to the contrary, it may likely be the first thing a potential reader will judge; and the cover must convey something about the text that it has been wrapped around. How does one select or create a single image, or even a cohesive set of images for a book? How literal or how abstract should the design be? Browse any bookshelf and you will see myriad strategies—some successful, some disastrous, others utterly baffling—to address this issue. Ray’s solution to this dilemma was rather innovative: rather than pressure himself with finding the image for a book, he bifurcated covers horizontally so that he had the freedom to work with multiple images. After reading a manuscript, he would find a set of matching or contrasting images, or even a more abstract image to pair with a literal image to create a tableau of sorts to entice a reader. The goal here was never to illustrate the book per se, but rather to arrest the reader’s eye and signal that the textual material within was challenging, unconventional, and likely sexy in new and thrilling ways. In addition to this bifurcation, Ray had a penchant for using wild, bright, occasionally sickly colors, wishing to evoke a certain sleazy 1970s aesthetic.

Ray was designing these covers at an interesting moment. On the one hand, the publishing industry was paying more attention to certain aspects of cover design for B-format paperbacks beginning in the late 1980s.1 And, only a bit after, simultaneous new developments from Apple Computers and Adobe Systems gave graphic designers a whole new set of tools to work with, ushering in a wild decade of experimental design. While Ray embraced this technology with gusto, he specifically tried to avoid making any of the High Risk covers appear to be computer generated. Whether or not he succeeded with that is an open question, and one I frankly cannot begin to answer. I love the covers—they were distinct at the time, especially when compared with the covers of other literary offerings, and they are still, to my mind, quite dazzling. The High Risk covers, taken as a group, have an unmistakably 1990s aesthetic to them and the many textures, images, and arresting colors are collaged and layered together do have an unmistakable frisson of the digital. However, from the vantage point of 2021, this potential “failure” on the part of Ray merely marks him as a luminary of computer-aided graphic design—much like his contemporary, Margo Chase, whose work is unmistakably of an era, yet persists far beyond it.

Ray was designing these covers at an interesting moment. On the one hand, the publishing industry was paying more attention to certain aspects of cover design for B-format paperbacks beginning in the late 1980s.1 And, only a bit after, simultaneous new developments from Apple Computers and Adobe Systems gave graphic designers a whole new set of tools to work with, ushering in a wild decade of experimental design. While Ray embraced this technology with gusto, he specifically tried to avoid making any of the High Risk covers appear to be computer generated. Whether or not he succeeded with that is an open question, and one I frankly cannot begin to answer. I love the covers—they were distinct at the time, especially when compared with the covers of other literary offerings, and they are still, to my mind, quite dazzling. The High Risk covers, taken as a group, have an unmistakably 1990s aesthetic to them and the many textures, images, and arresting colors are collaged and layered together do have an unmistakable frisson of the digital. However, from the vantage point of 2021, this potential “failure” on the part of Ray merely marks him as a luminary of computer-aided graphic design—much like his contemporary, Margo Chase, whose work is unmistakably of an era, yet persists far beyond it.

Still, Ray was clearly at the vanguard of commercial book design. Scholder claims that High Risk was the first press to make heavy use of horizontally bifurcated covers. Whether or not this is true is difficult to assess—and perhaps entirely beside the point—but as early as 1996 or 1997 one can notice larger publishers opting for both horizontally bifurcated covers and arresting color pallets. The most amusing example I have come across so far was the cover for the 1997 English translation of W.G. Sebald’s The Emigrants, published by New Directions. Sebald’s elliptic, melancholic narratives present no obvious point of entry for a designer, so a New Directions designer split the cover between a tree and an image of railroad tracks, all printed in an orange and blue wash. High Risk’s influence at work? I would heartily say yes, though it is an open question.

IV. Looking at the Covers

As mentioned previously, In My Room and its festive butt plugs were my very first taste of High Risk, but there are many more wonders to consider.

As mentioned previously, In My Room and its festive butt plugs were my very first taste of High Risk, but there are many more wonders to consider.

Continuing an aggressively gay theme, let us consider Renaud Camus’ Tricks: 25 Encounters. Viewed from a slight distance, both the top and bottom portion of this cover are occupied by a forceful, viscous eruption. Resembling both a heavily stylized money shot, as well as a torrent of mucous, or even perhaps a cluster of replicating virus cells, the green-yellow pallor of the top panel and the amber-snot pallor of the bottom forcefully suggest infection. Closer inspection of these mirrored torrents reveals a clever collage of attractive, muscled men straight out of an AMG (American Model Guild) rag. Highly appropriate, given that Tricks is a collection of Camus’ own experiences cruising—that is, the picking up of strangers, usually in public places, for anonymous or semi-anonymous fucking—in and around various cities.

This text has an interesting, complex history. In the first place, Camus captures a snapshot of a lost world. Many of the bars and baths, to say nothing of the culture of cruising in public parks and bathrooms, simply disappeared during the AIDS crisis. A few vestiges of this world linger in the United States, albeit in a very impoverished, denuded form. This book first saw publication in France in 1977 (featuring preface by sensual queen of melancholia and signification herself, Roland Barthes!), and was translated into English in 1981 by Richard Howard, well before AIDS was really on anybody’s radar. In 2021, Tricks could read as—and perhaps was—a personal archive of encounters and an edgy piece of autofiction. But how to read it in 1996, the year that High Risk republished it? 1995 was one of the deadliest years for AIDS patients. By this point the queer community had been thoroughly devastated both by the disease itself as well as the callous, murderous indifference of the state, and the very spaces that Camus wrote about in Tricks had simply vanished. In a world where censorious bigots like Andrew Sullivan were able to become the face of responsible, respectable public-facing gay behavior, High Risk’s publication of this particular text was a daring, provocative gesture. Recontextualized for the Plague Years, this book and its tantalizing cover ask the question of what—if any—sorts of hedonism should one enjoy during a crisis?

I would be remiss to not include a few thoughts on Renaud Camus himself, especially since I have gone out of my way twice, soon to be thrice, in this piece of writing to mention just how much of an insufferable, bigoted little shit Andrew Sullivan is. In a way, both men are of a pair, though Camus doesn’t appear to have any compunction about offending the prissy, bourgeois sensibilities that Sullivan finds himself enthralled to. Camus is a notorious figure in far-right French politics and is a proponent and theorist of the racist, Islamophobic theory of the “Grand Remplacement,” or “Great Replacement,” which contends that non-white, usually Arab Muslims, are engaged in a long project to overtake countries like France through migration and demographic replacement. This theory has some antecedents in Jean Raspail’s 1973 novel Le Camp des Saints, as well as British politician Enoch Powell’s notorious 1968 “Rivers of Blood” speech, though it really is just another iteration of pervasive, bigoted anxieties that have plagued white colonizer societies for centuries. Unsurprisingly, Camus is a supporter of French politician Marine Le Pen and has begun to have an influence with certain right-wing elements in the United States. While this might seem like something of a stark contrast to the figure who wrote Tricks, perhaps it is worth reflecting that, as much as one would hope, one’s libertine sexuality and openness to new encounters in one facet of their life in no way dictates what that person’s politics might be.

Next is Hervé Guibert’s to the friend who did not save my life. I confess that, while I adore Guibert, it took me five attempts to get through this nominally autobiographical novel, which chronicles both the narrator’s discovery that he has AIDS, as well as a vivid portrait of his physical decline. Most detailed discussions of medical issues leave me incredibly squeamish, so Guibert’s matter-of-fact descriptions of T-Cell count, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia’s effects on the lungs, brain cysts, painful sores developing on the throat, brutal side effects of AZT, hunting for new lesions on one’s own body, etc. were simply too much for me, though that effect may have been deliberate. But even worse is the description of his own mental isolation—the knowledge that one’s death is approaching quickly, easily indexed by the withering away of one’s own body, rapidly shifts the tenor of one’s social relations. Focused on his impending death, Guibert simultaneously is able to write like a detached alien observer and get bogged down so deeply in the petty minutiae of occupying a body. Particularly jarring and memorable are the ways in which the narrator occasionally treats his friend Muzil (a stand-in for Michel Foucault), who has a much more advanced form of the disease. Visits to Muzil’s hospital room quickly become unbearable—the room reeks of fried fish, he is constantly coughing and spitting into a plastic bin at the behest of a nurse, all in between being poked and prodded for various invasive tests. A goodbye kiss on the hand that the narrator gives to Muzil induces panic, and he leaves for home to vigorously wash his lips and mouth despite sharing the same disease as his friend. There’s no indication that the narrator himself shares any of the damaging paranoia that society at large had regarding physical contact with AIDS patients, though he occasionally treats both himself and other infected people as othered and potentially dangerous in their rapid decay from the disease.

Next is Hervé Guibert’s to the friend who did not save my life. I confess that, while I adore Guibert, it took me five attempts to get through this nominally autobiographical novel, which chronicles both the narrator’s discovery that he has AIDS, as well as a vivid portrait of his physical decline. Most detailed discussions of medical issues leave me incredibly squeamish, so Guibert’s matter-of-fact descriptions of T-Cell count, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia’s effects on the lungs, brain cysts, painful sores developing on the throat, brutal side effects of AZT, hunting for new lesions on one’s own body, etc. were simply too much for me, though that effect may have been deliberate. But even worse is the description of his own mental isolation—the knowledge that one’s death is approaching quickly, easily indexed by the withering away of one’s own body, rapidly shifts the tenor of one’s social relations. Focused on his impending death, Guibert simultaneously is able to write like a detached alien observer and get bogged down so deeply in the petty minutiae of occupying a body. Particularly jarring and memorable are the ways in which the narrator occasionally treats his friend Muzil (a stand-in for Michel Foucault), who has a much more advanced form of the disease. Visits to Muzil’s hospital room quickly become unbearable—the room reeks of fried fish, he is constantly coughing and spitting into a plastic bin at the behest of a nurse, all in between being poked and prodded for various invasive tests. A goodbye kiss on the hand that the narrator gives to Muzil induces panic, and he leaves for home to vigorously wash his lips and mouth despite sharing the same disease as his friend. There’s no indication that the narrator himself shares any of the damaging paranoia that society at large had regarding physical contact with AIDS patients, though he occasionally treats both himself and other infected people as othered and potentially dangerous in their rapid decay from the disease.

What might this have to do with the book cover? On the top half, there is a largely blue image of a figure seated on an institutional bed, hunched over and presumably staring at the floor. This image has something of a Beckettian quality to it, and its use for the cover for this particular work shouldn’t be surprising. The bottom half of the cover appears to be a piece of red metal, wet and bubbling from some sort of corrosion. It’s a disgusting image, and one that kept flaring up in my mind, mutating and expanding during my many attempts to read this book—it has a visceral quality to it, reminiscent of both the puritanical STI slide shows shown to many high school sex ed students in the United States, as well as the walls or floors of an active abattoir. Two simple images placed together help to capture the many complex dynamics Guibert’s narrative without being overbearing.

Two book covers for Lydia Davis, which stand in stark contrast to the bombastic, colorful examples mentioned above, will round out this small tour through High Risk’s offerings. The End of the Story and Break it Down, both published in 1996 are quiet, unassuming affairs. The former pairs a bland green panel with an image of nondescript chair with blue upholstery; the latter pairs a dark purple panel with an image of an illuminated lamp on a nightstand next to a bed in what appears to be a shabby motel. I confess to not having read quite as much of Davis’ work as many of my friends, though her absolute mastery of English grammar—much like Joy Williams and William Sloane III—allows her to transform the most mundane objects and experiences into the bizarre and unrecognizable. Cows, frozen peas, cremated remains (specifically their portmanteau, cremains), maids running vacuum cleaners, all become unrecognizable and even profound through Davis’ prose. Though these covers are muted, they still draw attention to themselves—something in the images is too studied, too bland, and urges investigation.

Two book covers for Lydia Davis, which stand in stark contrast to the bombastic, colorful examples mentioned above, will round out this small tour through High Risk’s offerings. The End of the Story and Break it Down, both published in 1996 are quiet, unassuming affairs. The former pairs a bland green panel with an image of nondescript chair with blue upholstery; the latter pairs a dark purple panel with an image of an illuminated lamp on a nightstand next to a bed in what appears to be a shabby motel. I confess to not having read quite as much of Davis’ work as many of my friends, though her absolute mastery of English grammar—much like Joy Williams and William Sloane III—allows her to transform the most mundane objects and experiences into the bizarre and unrecognizable. Cows, frozen peas, cremated remains (specifically their portmanteau, cremains), maids running vacuum cleaners, all become unrecognizable and even profound through Davis’ prose. Though these covers are muted, they still draw attention to themselves—something in the images is too studied, too bland, and urges investigation.

V. Some Closing Thoughts

Unfortunately, High Risk was not long for the world. Ayrton closed the operation’s New York office in 1997, prompting Silverberg to announce to trade publications that the imprint had folded. Books produced by Scholder, Silverberg, and Ray continued to appear into 1998 with Serpent’s Tail occasionally using the High Risk brand and some of its stylings after the departure of both Scholder and Silverberg, however the effect simply wasn’t the same. While High Risk managed to launch the careers of a number of writers, and established Amy Scholder as a formidable figure in the publishing world, the imprint seemed to fade from memory rather quickly.

Now might be just the moment to revisit the legacy of High Risk. Born out of the tumult of the AIDS crisis, I think it is worth asking what it is we can learn from the High Risk project today. History doesn’t repeat itself necessarily, but it is prone to echoes and rhymes. As I write this in 2021, the world is still in the grip of a catastrophic pandemic which has laid bare crises of capitalism as a viable mode of production, the inability of a sclerotic and rotting American empire to perform the bare minimum of governance and care, and given us a glimpse of the many horrors that await us as climate change proceeds unabated. I don’t mean to suggest that new avant garde publications will solve the big, intractable problems looming over us as a society, though cultural production does not happen in a vacuum and can in fact be symptomatic of larger structural forces in our lives. To paraphrase Amy Scholder and Ira Silverberg, let us instead consider how COVID-19 has impacted and transformed our lives, and what it will continue to mean for us as we move forward and live, create, and exist alongside one another.

Some notes & acknowledgements

This piece was reformatted and re-worked from a paper and research project done for Dr. Maite de Zubiaurre and Dr. Laure Murat’s Spring 2019 graduate seminar on the history of the book cover (German 263) at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Investigating High Risk presented a number of challenges—some interesting, others frustrating. While this imprint was particularly influential on small press publishing, nothing substantive has been written about it. Many of the articles mentioning its existence tend to focus on Ira Silverberg, who is a fixture in the New York publishing world and is a frequent person of interest due to his connections with William S. Burroughs. Less attention is paid to Amy Scholder, Rex Ray, or the history of the imprint itself, nor its contemporary reception. A collection of papers pertaining to High Risk’s operations have been deposited at the Fales Library at New York University. These have been difficult to access because I had neither the time nor funding while at UCLA to go visit; more recently, consulting archives have been complicated by COVID-19. Scholder deposited Rex Ray’s papers at the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. To my knowledge, this collection has not been processed, meaning that it is largely unavailable to researchers. Being a trained archivist myself, I would love to process and catalogue this collection, though that would require negotiation with staff at Bancroft, as well as a fair amount of grant (or donor) money to fund my work. Making this work available is of particular importance, as one of the biggest gaps in my research to date has been the life and work of Rex Ray himself. I hope to address this lacuna someday—I have a feeling that my work is not yet done with respect to High Risk.

This project would not have been possible without the collaboration of Amy Scholder, so I would like to thank her for her generosity. Graduate students can be a bit of a handful, but Amy was kind enough to talk with me for hours about High Risk, and invite me into her home to look at some of Rex’s other work. I would’ve never been able to get in touch with Amy had Kevin Killian not been gracious enough to introduce us. Kevin had been a fixture in my life since meeting him during my internship with Publication Studios in Portland, OR nearly a decade ago. Talking with him over the years helped give a context and depth to many writers published by High Risk, as many of them were old friends to him. In fact, it seems like Kevin knew absolutely everyone, and it’s hard to not feel his absence as I write this. Few people of his stature have been so warm and nurturing to goofy, well-meaning queers with intellectual aspirations. He was a keen intellect and bon viveur, and ought to be a model for us all. Neither writing nor scholarship happen in a vacuum—they are always community efforts and as such, I owe a debt of gratitude to so many for helping bring this history together even if I have not named them here.

Partial Bibliography

Ayrton, Pete. “About Serpent’s Tail – Serpent’s Tail Books,” n.d. [link].

Eldridge, David, Stuart Brill, Rex Ray, Angus Hyland, David Redhead, and The Senate. “The 30-Second Sell: Eight-Page Illustrated Feature on Paperback Book Cover Design, Including Interviews with The Senate, Rex Ray, Angus Hyland.” Eye Magazine, Autumn 1995. [Link].

Kaiser Family Foundation. “The HIV/AIDS Epidemic in the United States: The Basics.” kff.org, March 25, 2019. [Link].

Kollias, Hector. “Guillaume Dustan, Master of the Drive.” Journal of Romance Studies 8, no. 2 (2008): 113-.

Murphy, Tim. “AIDS’ Patient Zero Is Finally Innocent, But We’re Still Learning Who He Was.” New York Magazine, October 31, 206AD. [Link].

Peltier, Elian, and Nicholas Kulish. “A Racist Book’s Malign and Lingering Influence.” The New York Times, November 22, 2019, sec. Books. [Link].

Scholder, Amy. “AIDS, Cultural Life, & the Arts.” City Lights Review, 7–56. 2. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1988.

Ibid, Interview, May 14, 2019.

Scholder, Amy, and Ira Silverberg. “Introduction.” High Risk: An Anthology of Forbidden Writings, xii–xviii. New York and London: Plume Book, 1991.

Caleb Allen is an archivist and independent scholar currently living in Los Angeles.